The Commons

The commons

is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. These resources are held in common, not owned privately. Commons can also be understood as natural resources that groups of people (communities, user groups) manage for individual and collective benefit. Characteristically, this involves a variety of informal norms and values (social practice) employed for a governance mechanism. Commons can be also defined as a social practice of governing a resource not by state or market but by a community of users that self-governs the resource through institutions that it creates. Wikipedia

These days more and more people are taking matters into their own hands. Living in a ‘commune’ is even starting to become popular. These people see the usefulness of shared land, but also in the city people realise that the air that humanity breathes is for everyone. And shouldn’t it just be clean?! Like-minded people speak up and make it clear what they stand for. If it becomes clear that the government has not changed the situation, a possible next step is to break free from this government and thus solve any problems yourself, together.

The power of the commons as a free, fair system of provisioning and governance beyond capitalism, socialism, and other -isms. From co-housing and agro ecology to fisheries and open-source everything, people around the world are increasingly turning to ‘commoning’ to emancipate themselves from a predatory market-state system. Free, Fair, and Alive presents a foundational re-thinking of the commons – the self-organized social system that humans have used for millennia to meet their needs. Free, Fair and Alive by David Bollier

THE TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS The tragedy of the commons is a theory, that shared good will never last for future generations because the individual man will act independently and do every thing to full fill his own needs. In an issue of Science in 1968, the American ecologist Garrett Hardin (1915 – 2003) became famous for this critical look on the concept of the commons:

”As a rational being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain. Explicitly or implicitly, more or less consciously, he asks, “What is the utility to me of adding one more animal to my herd?” This utility has one negative and one positive component.

1) The positive component is a function of the increment of one animal. Since the herdsman receives all the proceeds from the sale of the additional animal, the positive utility is nearly +1.

2) The negative component is a function of the additional overgrazing created by one more animal. Since, however, the effects of overgrazing are shared by all the herdsmen, the negative utility for any particular decision-making herdsman is only a fraction of –1.”

The Americal political economist Elinor Ostrom (1933 – 2012) won the nobel prize for economy in 2009 for disproving the theory of Garrett Hardin. She proved that thinking and working as a community and for the future does leed to more efficient outcomes. She did research on smaller communes where people were faced with problems and had solved these between themselves. She discovered that caring for the commons had to be a multiple task, organised from the ground up and shaped to cultural norms. It had to be discussed face to face, and based on trust.

Ostrom identified eight “design principles” of stable local common pool resource management:

Clearly defined (clear definition of the contents of the common pool resource and effective exclusion of external un-entitled parties); The appropriation and provision of common resources that are adapted to local conditions; Collective-choice arrangements that allow most resource appropriators to participate in the decision-making process; Effective monitoring by monitors who are part of or accountable to the appropriators; A scale of graduated sanctions for resource appropriators who violate community rules; Mechanisms of conflict resolution that are cheap and of easy access; Self-determination of the community recognized by higher-level authorities; and In the case of larger common-pool resources, organization in the form of multiple layers of nested enterprises, with small local CPRs at the base level.

MY OWN DEFINITION The common is that what we share and use together. It is a shared good like a piece of land, a pond, forest or objects like a bicycle or washing machine for which everybody takes responsibility. This allows the people who share this object or space to use it. But divide and share potential produce, decision-making or consequences evenly to prevent overuse and exhaustion. Collaborating over a common good works best when people set up rules together on which they all agree, participatory decision-making is vital.

There is some skepticism about the commons, especially by our current political paradigm where they talk about ‘The tragedy of the commons’. They fear that if no one takes responsibility and tries to optimize the situation for themselves it is bad for the whole community.

For example, if a community would own a fishing lake and everyone would just take out the fish for themselves, the lake would be empty in no time. But when rules are made where every person takes one fish and leaves the rest, the fish will have time to multiply and the people would be able to fish for years in a row.

So, short term self-interest of people makes everyone suffer in the long run. As to when collectively taken care of a property the lifespan might prolong.

LINKS:

- Freerange vol.7 The commons: We are commoners, creative, distinctive individuals inscribed within larger wholes. We may have many unattractive human traits fueled by individual fears and ego, but we are also creatures entirely capable of self-organisation and cooperation; with a concern for fairness and social justice; and willing to make sacrifices for the larger good and future generations.

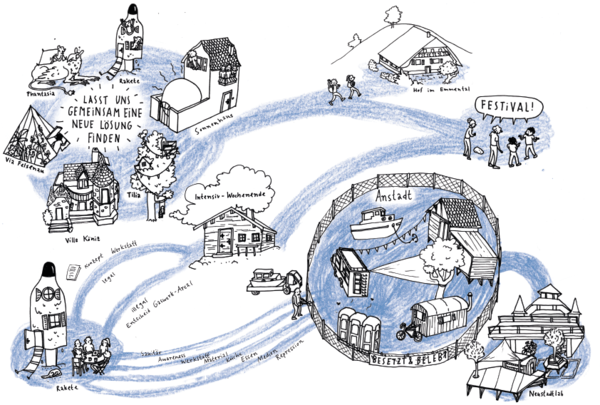

- Anstadt –> Last summer I went to Switzerland for the first time. We met young people in the capital city of Bern. We started talking and they said that they lived on a piece of land next to the river Aare. We were allowed to park our camper there for a night and were faced with a nice surprise. The piece of land was managed by about 15 people. They all had built houses here together and laid out a large garden in which they all worked. This commune originated from many years of squatting. In the end, the municipality had given permission that, if the residents came up with a good plan, they could continue to live here. Later I found their plan online: PDF

- Bellingcat is an online organization in which citizens search for the truth behind the news. A lot of information can be found online thanks to videos filmed with mobile phones, links to websites or articles. The founders of Bellingcat questioned the authenticity of the news they heard and investigated themselves. They used google maps to check location data and asked people from other countries they had met online to go to this location and verify information. They opened a website in which they asked native speakers to translate text. In the meantime, Bellingcat has grown into a worldwide community of online networkers and together they are looking for real and fake news. Bellingcat – Truth in a post truth world

- Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that helps overcome legal obstacles to the sharing of knowledge and creativity to address the world’s pressing challenges. They provide Creative Commons licenses and public domain tools that give every person and organization in the world a free, simple, and standardized way to grant copyright permissions for creative and academic works; ensure proper attribution; and allow others to copy, distribute, and make use of those works. The Creative Commons

CITATIONS

- Hardin, Garrett. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 13 Dec. 1968, science.sciencemag.org/content/162/3859/1243.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Elinor Ostrom”. Wikipedia, 10 oktober 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elinor_Ostrom.

- Bollier, David. “Free, Fair and alive.org/read-it”. http://www.freefairandalive.org, 3 september 2019, http://www.freefairandalive.org/read-it.

- “When We Share, Everyone Wins.” Creative Commons, 25 Sept. 2020, creativecommons.org/.

- Higgins, Eliot. “The Home of Online Investigations.” Bellingcat, 2012, http://www.bellingcat.com/.

- Angus, Ian. “Ian Angus, The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons, 2008.” Et Vous N’avez Encore Rien Vu…, 18 Apr. 2016, sniadecki.wordpress.com/2016/04/18/angus-mythe-en/.