Difference between revisions of "Wheelshare"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | Wheelshare | |

| − | + | Author: Wietske Lutgendorff | |

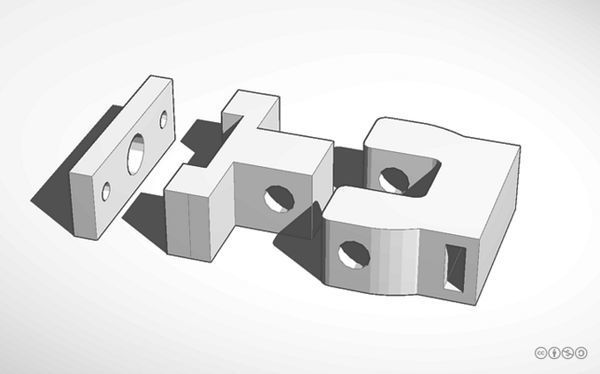

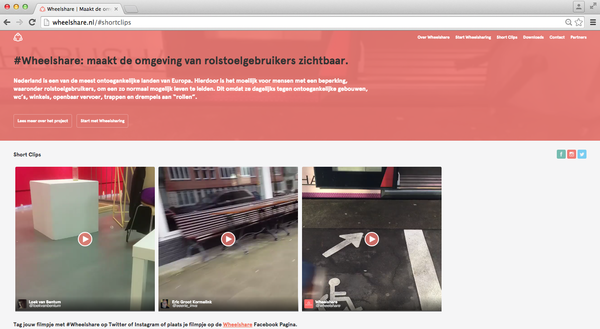

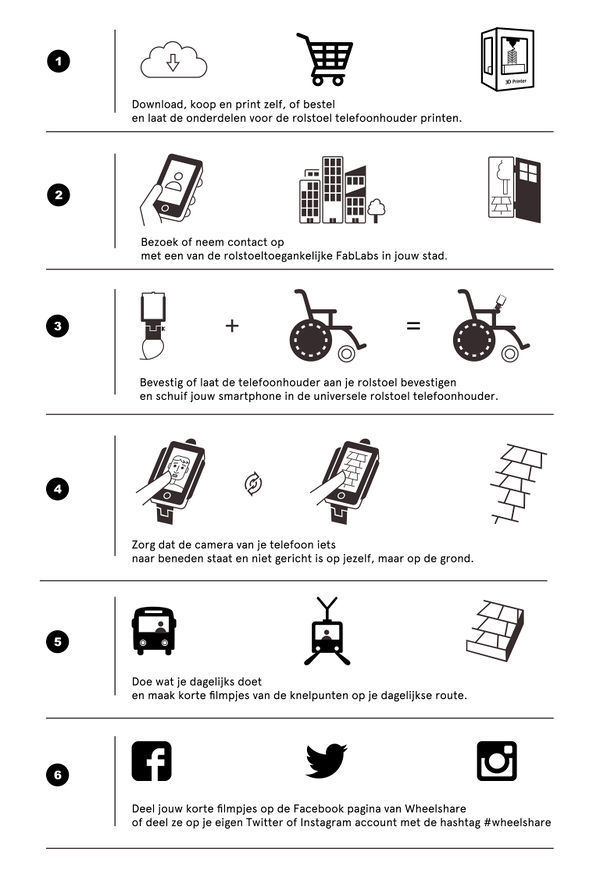

| − | + | There are currently 2.3 million people with disabilities living in the Netherlands. Ten years after the 2006 United Nations convention on the rights of disabled people, little has changed in the Netherlands; we have actually become one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe. This makes it difficult for people with disabilities, including wheelchair users, to lead a life which is as normal as possible. This is because they must deal on a daily basis with inaccessible buildings, toilets, shops, public transportation, stairs and thresholds. The project Wheelshare is based on the fact that wheelchair users feel visible for the wrong reasons, but that they also know better than anyone else which places are the most inaccessible. Wheelshare provides them with a device for attaching their cellphone to their wheelchair in order to film their experiences. It also provides an online platform for collecting, presenting and sharing these experiences. By using the hashtag #Wheelshare, these films and photos are collected automatically on the Wheelshare Facebook page. | |

| + | |||

| + | Website: www.wheelshare.nl | ||

| + | Facebook: www.facebook.com/wheelshareNL | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why wheelchairs | ||

| + | It is estimated that one in 8 people in the Netherlands is dealing with a long-term disability (Statistics Netherlands, 2008). Not every restriction is the same; disabilities can be physical, psychological, mental, intellectual or sensory. For example, someone with a disability can be deaf or blind, or suffer from mobility problems. In the Netherlands it is not known exactly how many people with disabilities use a wheelchair. The publication ‘Joining Limitations’ has calculated that there are approximately 225,000 to 250,000 people who need to use a wheelchair in the Netherlands (SCP, 2012). These numbers are likely to increase rapidly in the coming years, partly due to the aging population. I myself also need to use a wheelchair. | ||

| + | The Netherlands: one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe | ||

| + | The Netherlands unfortunately is not prepared for this development, and is currently one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe for people with disabilities. Despite a convention drawn up by the United Nations in 2006 for the rights of people with disabilities, little has changed in ten years in the Netherlands. This makes it difficult for people with disabilities, including wheelchair users, to lead a normal life. This is because they have to deal on a daily basis with inaccessible buildings, toilets, shops, public transport, stairs and thresholds. For those who are ‘healthy’ or are simply able to walk, it’s hard to imagine how and where it is so inaccessible in the Netherlands. Also, it’s hard to imagine what should change exactly (often small solutions which can already provide a substantial improvement). | ||

| + | Claim making power | ||

| + | I began the project Wheelshare by conducting several interviews with wheelchair users. Wheelshare is an open concept, consisting of a platform and a toolkit, and making it possible to demonstrate the obstacles that impede us from free access and movement. The images may yield new insights and will always be created and shared by the wheelchair user. This not only presents a realistic picture of the daily experiences of the person with a disability, but the images can also be used as educational materials. The pictures can bring us a step closer to an inclusive and accessible society, because together we can identify bottlenecks which were not previously visible. | ||

| + | Discussion | ||

| + | The editorial board invites readers to reflect and react on the following questions: | ||

| + | Documenting and collecting material is one thing; the artistic application of this rough material, and presenting it to a wider public is another matter. How could this important initiative be brought to the next stage? Furthermore: the resource group is now only documenting their problems. What about documenting their creative solutions? Do you know inspiring examples? Please let us know. | ||

| + | [[Category:Explore]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Empowerment]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Democratisation]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wietske Lutgendorff | ||

| + | Wietske Lutgendorff is an Advertising / Open Design student. She positions herself as a professional problem solver because she continuously has to adapt to her environment by living with a disability. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 00:04, 8 July 2016

Wheelshare Author: Wietske Lutgendorff There are currently 2.3 million people with disabilities living in the Netherlands. Ten years after the 2006 United Nations convention on the rights of disabled people, little has changed in the Netherlands; we have actually become one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe. This makes it difficult for people with disabilities, including wheelchair users, to lead a life which is as normal as possible. This is because they must deal on a daily basis with inaccessible buildings, toilets, shops, public transportation, stairs and thresholds. The project Wheelshare is based on the fact that wheelchair users feel visible for the wrong reasons, but that they also know better than anyone else which places are the most inaccessible. Wheelshare provides them with a device for attaching their cellphone to their wheelchair in order to film their experiences. It also provides an online platform for collecting, presenting and sharing these experiences. By using the hashtag #Wheelshare, these films and photos are collected automatically on the Wheelshare Facebook page.

Website: www.wheelshare.nl Facebook: www.facebook.com/wheelshareNL

Why wheelchairs It is estimated that one in 8 people in the Netherlands is dealing with a long-term disability (Statistics Netherlands, 2008). Not every restriction is the same; disabilities can be physical, psychological, mental, intellectual or sensory. For example, someone with a disability can be deaf or blind, or suffer from mobility problems. In the Netherlands it is not known exactly how many people with disabilities use a wheelchair. The publication ‘Joining Limitations’ has calculated that there are approximately 225,000 to 250,000 people who need to use a wheelchair in the Netherlands (SCP, 2012). These numbers are likely to increase rapidly in the coming years, partly due to the aging population. I myself also need to use a wheelchair. The Netherlands: one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe The Netherlands unfortunately is not prepared for this development, and is currently one of the most inaccessible countries in Europe for people with disabilities. Despite a convention drawn up by the United Nations in 2006 for the rights of people with disabilities, little has changed in ten years in the Netherlands. This makes it difficult for people with disabilities, including wheelchair users, to lead a normal life. This is because they have to deal on a daily basis with inaccessible buildings, toilets, shops, public transport, stairs and thresholds. For those who are ‘healthy’ or are simply able to walk, it’s hard to imagine how and where it is so inaccessible in the Netherlands. Also, it’s hard to imagine what should change exactly (often small solutions which can already provide a substantial improvement). Claim making power I began the project Wheelshare by conducting several interviews with wheelchair users. Wheelshare is an open concept, consisting of a platform and a toolkit, and making it possible to demonstrate the obstacles that impede us from free access and movement. The images may yield new insights and will always be created and shared by the wheelchair user. This not only presents a realistic picture of the daily experiences of the person with a disability, but the images can also be used as educational materials. The pictures can bring us a step closer to an inclusive and accessible society, because together we can identify bottlenecks which were not previously visible. Discussion The editorial board invites readers to reflect and react on the following questions: Documenting and collecting material is one thing; the artistic application of this rough material, and presenting it to a wider public is another matter. How could this important initiative be brought to the next stage? Furthermore: the resource group is now only documenting their problems. What about documenting their creative solutions? Do you know inspiring examples? Please let us know.

Wietske Lutgendorff Wietske Lutgendorff is an Advertising / Open Design student. She positions herself as a professional problem solver because she continuously has to adapt to her environment by living with a disability.