Difference between revisions of "The New Rotterdam Folk Story"

Rümeysa Önal (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Article | |

| + | |Image=hnrv1.jpg | ||

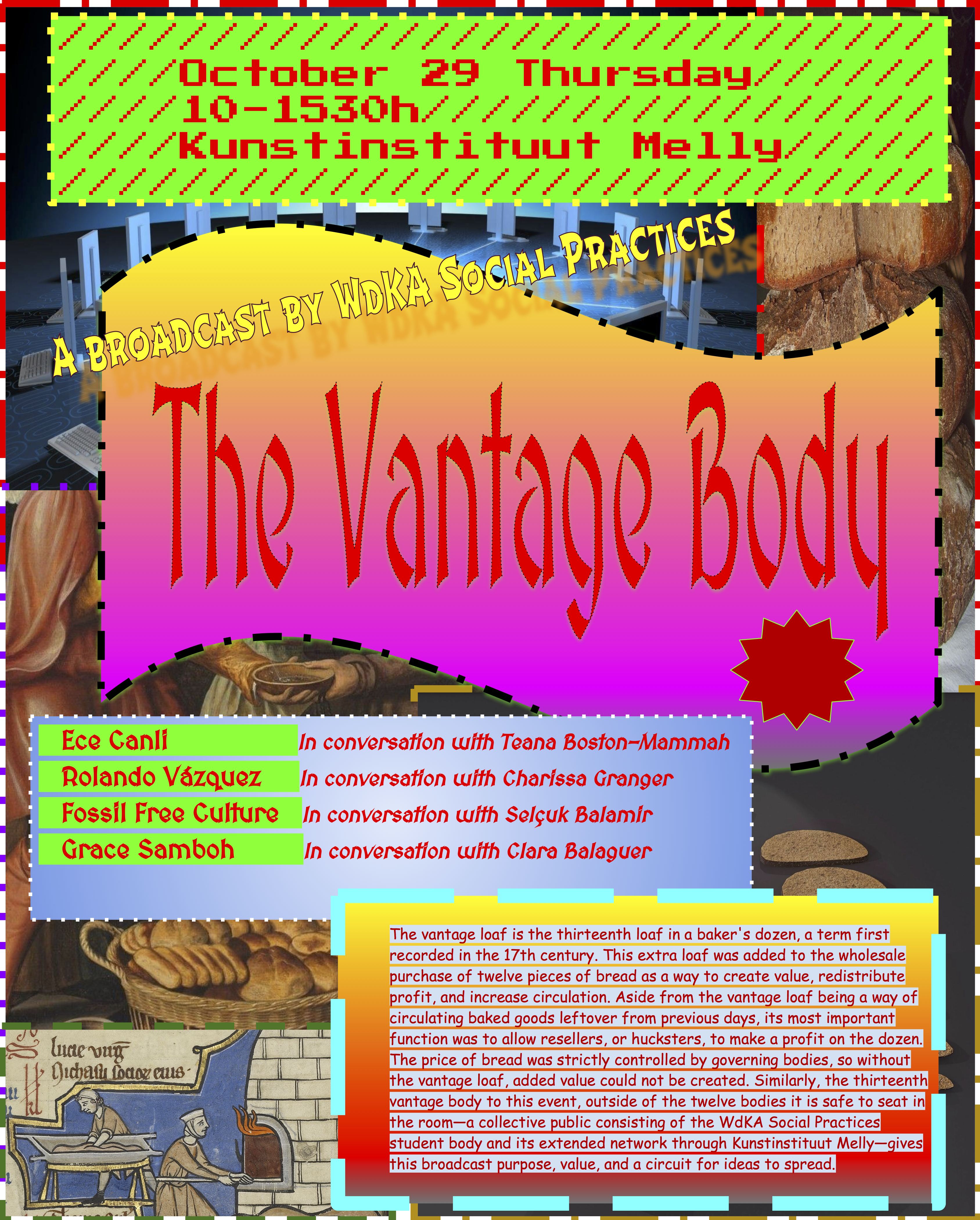

| + | |Caption=Aron Dijkstra drawing in the Kitchen of Het Verhalenhuis | ||

| + | |Summary=With the development of modern technologies such as mobile phones and social media, many people in the early 21st century have argued that 'storytelling is dead' in Western society. People read fewer books; children and teenagers are increasingly unable to listen to someone talk for more than 30 minutes; tribes and their oral traditions are almost entirely extinct. And yet we continue to tell each other stories, in different forms, adapted to a new pace and with brand-new, but also well-known, even old-fashioned, means. Designers and artists are able to tell stories in ways that are suitable to our modern, supersaturated society. The project 'The New Rotterdam Folk Story' attempts to do so with an online collection of stories celebrating the cultural diversity of the city of Rotterdam. | ||

| + | |Article=Author: Aron Dijkstra | ||

| − | + | == Bridging different islands == | |

| + | In my essay and graduation project, I describe the culturally diverse city of Rotterdam as an Archipelago City, a city consisting of many cultural and ethnic islands that participate in the same society but almost never mix. Also, the more politicians try to create a homogenous society, the more these islands tend to isolate themselves. The Archipelago City is defined by its diversity. As an illustrator interested in stories, I saw an opportunity to occupy a unique position between these social islands, and to visualise the stories of individuals from various groups in society. In doing so, I created an interesting collection of visualised personal stories, and made these available to a broader Rotterdam audience. | ||

| − | ==== | + | == Graphic novels in video clips == |

| − | + | The New Rotterdam Folk Story is a collection of personal stories from individuals from all over Rotterdam, visualised for an online and offline platform, as short graphic novels. These short visualisations re-tell the old fashioned oral day-to-day stories in a way that suits our modern society, so that it reaches more people and reminds us of the importance of the personal story. | |

| + | In The New Rotterdam Folk Story, I used portraits as a basis for short graphic novels, which I then further adapted into short video clips. This way I made use of two very recognisable and popular storytelling media. Also, I knew that these visual implementations would be more suitable for sharing in magazines and online. You can look at the stories on the Facebook page: www.facebook.com/Het-Nieuwe-Rotterdamse-Volksverhaal-654606788019517/ | ||

| − | + | == Drawing vs. photography == | |

| + | I collected these stories while drawing portraits of the participants. I did not use a recording device or camera. Drawing the portrait gave me about 20 minutes of quality time with the participant, in a relaxed and intimate atmosphere that would have been very different if I had used a film or photo camera. A camera is very direct and at the same time tends to create a distance between artist and subject, whereas a drawing establishes a more intimate connection and therefore creates a more emotionally connected visualisation. With drawings, the viewer does not only experience the representation of the drawing itself, but also the process of making it. I believe this experience is lost in photography, since we are so used to having cameras around us all the time. This effect is also felt in the world of journalism. Nowadays, illustrators are reclaiming a place in pictorial reportage and journalism, which was taken over almost entirely by photography in the early twentieth century. Illustrators are now joining journalists in conflict areas to visualise their experiences, or investigating and visualising politics and economy. Why? Images are quick message bearers, they aren't obstructed by language barriers and they reflect subjectivity: the artist's own experiences and opinion. News nowadays includes more opinion, commentary and analysis than it did, say, fifty years ago; it also includes more images. | ||

| − | + | == What's the point of storytelling? == | |

| + | Storytelling is as old as the human species. In his book 'On The Origins of Stories' (2010) the literary expert Brian Boyd describes how telling stories made prehistoric humans different from their ape-like cousins. Ancient cave paintings are well-known examples of an early human urge to express ideas about our surroundings and our place the world. Boyd argues that humans are uniquely evolved to communicate through representation, in language and in pictures. In other words: humans communicate through storytelling. | ||

| + | Modern society is supersaturated with stories. Whether or not we realise it, we are interacting with storytelling almost every minute of every day. Most of us are connected 24/7 to media such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Skype, Instagram and various news feeds, to say nothing of advertising. Though most of these adverts would make lousy bedtime stories, they are stories nonetheless. | ||

| + | So what is the point of storytelling? The most basic answer would be: there's no way we cannot tell stories. It's how we communicate feelings, norms and experiences. In short, the story is what makes a society what it is: broad and culturally diverse. A more relevant question would be whether storytelling still serves a purpose in generating social cohesion. I believe it does, though old-fashioned ways of storytelling (i.e. oral) may require a little assistance in order to reach the other cultural 'islands'. Using contemporary media and pictorial journalism to lift ordinary stories to the plane of folk stories, The New Rotterdam Folk Story enables personal storytelling by connecting the personal sphere to society, and by bringing society into the personal sphere. | ||

| − | + | ''Aron Dijkstra studied Illustration and Cultural Diversity at the WdKA in Rotterdam. The New Rotterdam Folk Story was shown in Het Verhalenhuis Belvédère, Rotterdam, in late summer 2015.'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:hnrv1.jpg|Me drawing in the Kitchen of Het Verhalenhuis]] | |

| − | |||

[[File:hnrv4.png|A portrait of a Rotterdammer]] | [[File:hnrv4.png|A portrait of a Rotterdammer]] | ||

| − | + | ||

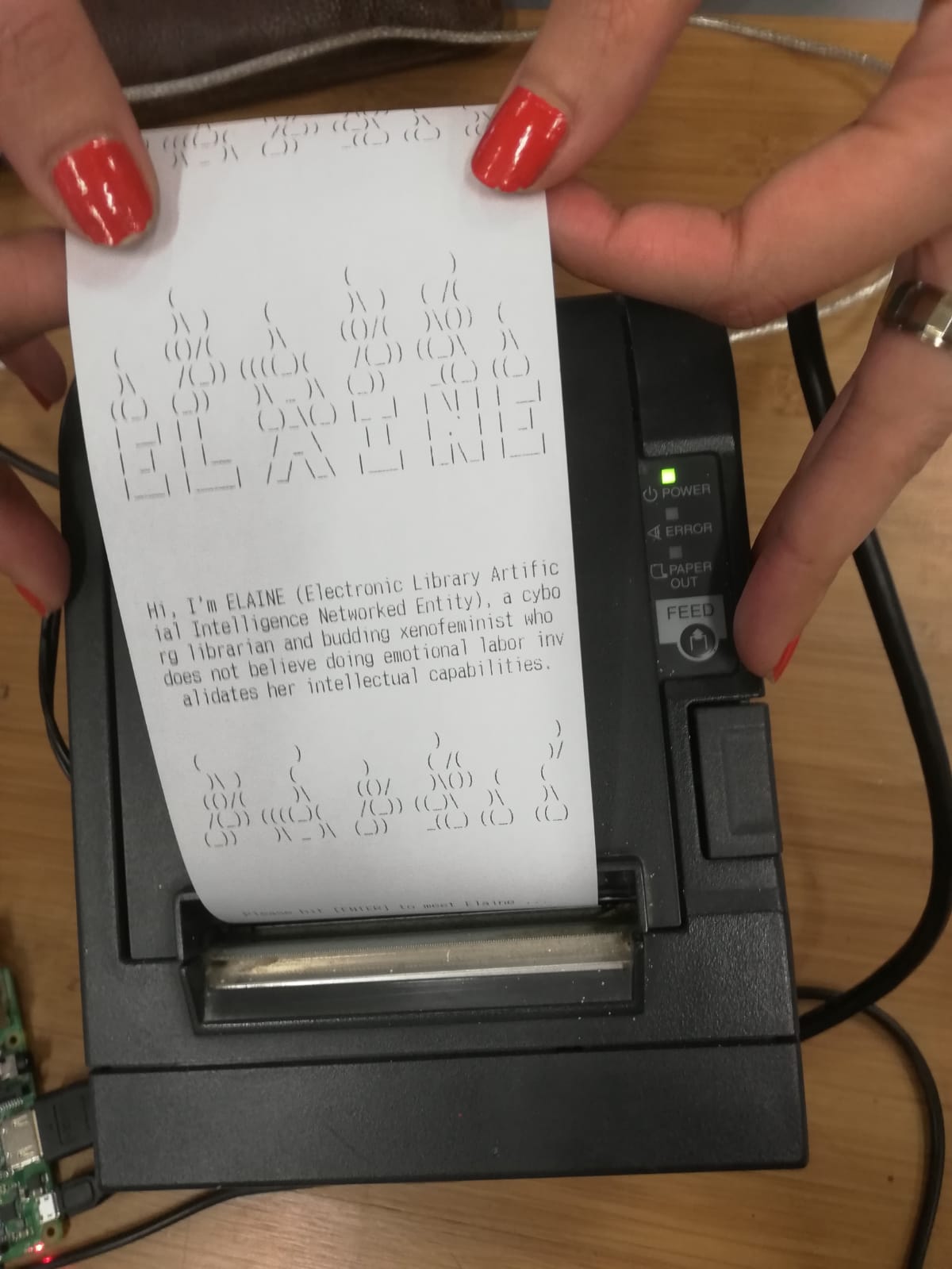

| + | [[File:hnrv5.png|A short picture story based on the portrait and story of a Rotterdammer]] | ||

| − | + | {{#ev:youtube|n9TWwG4SFWQ}} | |

| − | + | }} | |

| − | + | {{Category selector | |

| − | + | |Category=Illustration | |

| − | {{ | + | }} |

| − | + | {{Category selector | |

| − | + | |Category=Participation | |

| − | + | }} | |

| − | + | {{Category selector | |

| − | + | |Category=Diversity | |

| − | + | }} | |

| − | + | {{Articles more}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 21:29, 30 October 2018

Author: Aron Dijkstra

Bridging different islands

In my essay and graduation project, I describe the culturally diverse city of Rotterdam as an Archipelago City, a city consisting of many cultural and ethnic islands that participate in the same society but almost never mix. Also, the more politicians try to create a homogenous society, the more these islands tend to isolate themselves. The Archipelago City is defined by its diversity. As an illustrator interested in stories, I saw an opportunity to occupy a unique position between these social islands, and to visualise the stories of individuals from various groups in society. In doing so, I created an interesting collection of visualised personal stories, and made these available to a broader Rotterdam audience.

Graphic novels in video clips

The New Rotterdam Folk Story is a collection of personal stories from individuals from all over Rotterdam, visualised for an online and offline platform, as short graphic novels. These short visualisations re-tell the old fashioned oral day-to-day stories in a way that suits our modern society, so that it reaches more people and reminds us of the importance of the personal story. In The New Rotterdam Folk Story, I used portraits as a basis for short graphic novels, which I then further adapted into short video clips. This way I made use of two very recognisable and popular storytelling media. Also, I knew that these visual implementations would be more suitable for sharing in magazines and online. You can look at the stories on the Facebook page: www.facebook.com/Het-Nieuwe-Rotterdamse-Volksverhaal-654606788019517/

Drawing vs. photography

I collected these stories while drawing portraits of the participants. I did not use a recording device or camera. Drawing the portrait gave me about 20 minutes of quality time with the participant, in a relaxed and intimate atmosphere that would have been very different if I had used a film or photo camera. A camera is very direct and at the same time tends to create a distance between artist and subject, whereas a drawing establishes a more intimate connection and therefore creates a more emotionally connected visualisation. With drawings, the viewer does not only experience the representation of the drawing itself, but also the process of making it. I believe this experience is lost in photography, since we are so used to having cameras around us all the time. This effect is also felt in the world of journalism. Nowadays, illustrators are reclaiming a place in pictorial reportage and journalism, which was taken over almost entirely by photography in the early twentieth century. Illustrators are now joining journalists in conflict areas to visualise their experiences, or investigating and visualising politics and economy. Why? Images are quick message bearers, they aren't obstructed by language barriers and they reflect subjectivity: the artist's own experiences and opinion. News nowadays includes more opinion, commentary and analysis than it did, say, fifty years ago; it also includes more images.

What's the point of storytelling?

Storytelling is as old as the human species. In his book 'On The Origins of Stories' (2010) the literary expert Brian Boyd describes how telling stories made prehistoric humans different from their ape-like cousins. Ancient cave paintings are well-known examples of an early human urge to express ideas about our surroundings and our place the world. Boyd argues that humans are uniquely evolved to communicate through representation, in language and in pictures. In other words: humans communicate through storytelling. Modern society is supersaturated with stories. Whether or not we realise it, we are interacting with storytelling almost every minute of every day. Most of us are connected 24/7 to media such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Skype, Instagram and various news feeds, to say nothing of advertising. Though most of these adverts would make lousy bedtime stories, they are stories nonetheless. So what is the point of storytelling? The most basic answer would be: there's no way we cannot tell stories. It's how we communicate feelings, norms and experiences. In short, the story is what makes a society what it is: broad and culturally diverse. A more relevant question would be whether storytelling still serves a purpose in generating social cohesion. I believe it does, though old-fashioned ways of storytelling (i.e. oral) may require a little assistance in order to reach the other cultural 'islands'. Using contemporary media and pictorial journalism to lift ordinary stories to the plane of folk stories, The New Rotterdam Folk Story enables personal storytelling by connecting the personal sphere to society, and by bringing society into the personal sphere.

Aron Dijkstra studied Illustration and Cultural Diversity at the WdKA in Rotterdam. The New Rotterdam Folk Story was shown in Het Verhalenhuis Belvédère, Rotterdam, in late summer 2015.

Links

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.