Difference between revisions of "My whiteness doesn't mean nothing"

m (Text replacement - "{{GraduationYear selector |Year=2018 }}" to "{{Category selector |Category=2018 }}") |

|||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

|Category=Whiteness | |Category=Whiteness | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Category selector |

| − | | | + | |Category=2018 |

}} | }} | ||

{{Articles more}} | {{Articles more}} | ||

Revision as of 16:35, 14 June 2019

The wikipage input value is empty (e.g. SomeProperty::, [[]]) and therefore it cannot be used as a name or as part of a query condition.

My Whiteness Doesn't mean nothing

I moved to Rotterdam when I was 21 years old, being born in a rural area of Limburg. Growing up in a stable family environment, where all my school experiences from primary school till my MBO where predominately white. I decided to study Lifestyle at the art academy Willem de Kooning in Rotterdam, where in my second year I got my first experiences with the practice cultural diversity. Taking part in this practice for a period of three years gave me the opportunity to research and mainly observe other cultures in Rotterdam. These experiences triggered an interest and awareness about cultural differences and in-equality’s visible in the city that I became an inhabitant of. My interest in social research structures methodology made me decide to go study abroad in Boston USA. During my study-abroad I got confronted with topics like; Black lives matter, islamophobia and addressing privilege. Within the community of Lesley University, I have seen a different collectivity. I have been attending event where topics like; cultural identity, cross-cultural approaches in learning and teaching, social justice for all and inclusive diversity were on the top of the agenda of the University. It was only coming back to Rotterdam and the Willem de Kooning academy that made me realize that I have been part of this WDKA community for three years but going to America made me see how we don’t speak enough about diversity and race within our academy. I believe WdKA should continue the dialogue started by publishing ‘WDKA makes a difference’, on what is seen as ‘normal’ within our academy?’ I believe talking about race is important because in the public debate, discrimination and inequality on the basis of race, gender and religion are the order of the day and because I as many others moved to this culturally diverse and beautiful city, having no experience and knowledge about how to talk about race. Despite this, opinions about this are frequently shared, which also provides questions and divisions. Education therefore plays a crucial role in the social education of students. This role is part of the statutory task of schools and universities. [1] Educational institutions such as WdKA therefore have an exemplary function and can be a catalyst for change. I want to start this dialogue within the WdKA student community, to create awareness within the white community and empower the white individual art student to give shape to their identity, being part of a majority in a white institution talking about race. As a social practitioner, I show myself capable of relating to the larger constellation of our dominant white society [2] with its insistence on ‘white innocence’.[3] Through my experiences in the practice ‘cultural diversity’ I will eventually articulate my insights in terms of a critical expertise in the societal complexities of the Willem de Kooing academy. In this research paper I will confront the reader with the research question: How to create a basic level of awareness and knowledge about white privilege for students attending the WdKA? The driving force behind this question is not so much ‘why’ or ‘what’ has to be done but ‘how’ can it be done. It is a productive question where every open outcome will be relevant to construct a critical conclusion. To be able to create a design for this question I will discuss the following subjects, whiteness, institutional life and inclusive education. I will make use of a specific literature framework to test if through a particular intervention a tool can be established where a dialogue about white privilege and its influences in art education can be given shape.

Research area:

This research was conducted over the period of February to May 2018 at the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. According to statistics from WdKA’s own databank it shows that in 2016, of the 1.908 students 71% are classified as ‘autochtone’, 17% as western ‘allochtone’ and 13% as ‘non-western allochtone’. [4] Earlier research on the student population of the WdKA has been done by teacher researchers, Paul Pos, Not the usual suspects Rotterdam: Hogeschool Rotterdam Master Leren en Innoveren, 2014 Marleen van Arendonk, “Ik dacht dat de Academie alleen voor witte mensen was”, 2016 and Teana Boston-Mammah, WdKA makes a difference: The Entrance gap, 2016. The Willem de Kooning Academy is located in the center of Rotterdam, zooming out to the population of Rotterdam the city at last count has 638.466 residents. [5] The composition of this population is almost fifty-fifty with 313.634 ‘autochtone’ and 324.832 from diverse ethnic populations commonly talked about as ‘allochtone’. [6] Gloria Wekker places these two words in the Dutch context as Allochtonen meaning “those who came from elsewhere. ”Autochtonen meaning “ those who are from here” which as everyone knows, refers to white people.( White innocence, 2016:23) In ‘The Entrance gap’ Teana Boston-Mammah is drawing attention to the importance of how without being able to tap into the increasing number of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) students in Rotterdam it becomes increasingly difficult to obtain a certain level of funding as an institute. She questions how to maintain a narrative of cutting edge art & design courses when the majority of your students are from the suburbs and villages around Rotterdam who do not embody or experience themselves the bigger societal discourses. Through interviews cited in Pos (2014) and research conducted by Machteld de Jong in ‘Diversiteit in het hoger onderwijs’ (2014), Boston-Mammah shows that many of these students often come into contact with BME students and vice versa for the first time in higher educational learning environments. Whereas she refers to Pos who writes about the ambition of WdKA to be connected to the city of Rotterdam stems from its social responsibility to also provide social and economically marginalized groups opportunities to develop their talents in a higher educational art & design context. (Boston-Mammah, 2016:8) As mentioned in my introduction I myself was a student moving to Rotterdam form a village in Limburg. Having my first encounter with BME students in higher education, not knowing how to talk about race. Taking part in the practice Cultural Diversity for three years make me able to challenge my own position within the academy. During my Minor I challenged my own white embodiment in relation to the relevancy of exhibiting diversity in a white cube. In this research, I will use language in terms of talking about bodies and definitions of bodies; using the terms white and black or other bodies of color not as biological categories but as political and cultural concepts. I will follow Frankenberg’s conceptualization of whiteness, in that whiteness refers to “a set of locations that are historically, socially, politically and culturally produced, and, moreover are intrinsically linked to unfolding relations of domination. Naming whiteness displaces it from the unmarked, unnamed status that is itself an effect of its dominance”. (Wekker,2016:24) the concept of race is often applied in education debates around inclusion. Critical race theory (CRT) (Gilborn, 2008) is a relatively new conceptual approach but appears to be a valuable tool for working against discrimination in art education as it explores the effects of whiteness on learning. CRT takes as its starting point the notion that racism is ordinary: it is found in the system and practices of everyday life and is therefore very difficult to ‘cure or address’ (Hatton, 2015:5). I adopt CRT as a framework to challenge a more inclusive art education. Being fully aware that because of my focus on white students and whiteness the work I am going to make could be claimed rather excluding than including. I believe that without acknowledging the privileges of being white and researching the embedment of whiteness in WdKA’s educational system, we will not be able to talk about race within our academy and therefore inclusion cannot be achieved.

Literature review:

Whiteness: In the past few years there is an increasing level of public debate and interest in the topic White privilege in The Netherlands, see the work of Anousha Nzume, Hallo Witte Mensen, 2017 Gloria Wekker, White Innocence, 2016. In the states this awareness of white privilege and race privilege began in the eighties with the work of Peggy McIntoch, White privilege: Unpacking the invisible Knapsack, 1988 and Ruth Franken in White women Race Matters: the social construction of whiteness, 1993.

I ask the question: Is the concept “whiteness”, in a direct or indirect way, relevant to understand your (life)-experiences or identity? As most white people seem to be barely aware of their own color, let alone the role it plays in their lives. So, first of all I feel that it is important that “we” get used to think about it at bit more often. Based upon my reading and understanding of the book ‘Hallo witte mensen’ by Anousha Nzume, I will present several questions with which one can consider the roll of whiteness in one’s personal life.

1 What was the first time you realized you are white? 2 In what way did whiteness influence your puberty? 3 How many times a day do you get confronted with the fact that you are white? 4 How often do you stand still by the fact that your answers are not representative for people of color?

How often do you consider if the roll of whiteness in your personal life is related to your privileges? For me it is understandable, that we all have privileges that we are not aware of. So, let me first start with the simple overarching concept. What is privilege? Privilege according to Nzume means that things are systematically going easier for a whole group of people based upon boxes, in which box you are positioned is sometimes already determined for you, by social constructs (2017: p38). To create a better view on these social constructs in relation to whiteness I first looked at ‘The matter of whiteness’ in by Richard Dyer (‘White,1997) and the secondly at the ‘Cultural archive’ by Gloria Wekker (White innocence, 2016). Dyer points out that the unawareness of color by white people is the most powerful position, it is the position of being ‘just’ human. He claims that ‘the point of seeing the racing of whites is to dislodge them/us from the position of power, with all the inequities, oppression, privileges and sufferings in its train, dislodging them/us by undercutting the authority with which they/us speak and act in and on the world”. This assumption that white people are just people, which is not far off saying that whites are people whereas other colors are something else, is endemic to white culture. Some of the sharpest criticism of it has been aimed at those who would think themselves the least racist or white supremacist’ (Dyer,1997:2). As Dyer sees these social constructs as a position of being neutral, I will refer to Wekker who looks at these social constructs through our cultural archive which she refers to as ‘a repository of memory, in the heads and hearts of people in the metropolis, but its content is also silently cemented in policies, in organizational rules, in popular and sexual cultures, and in commonsense everyday knowledge, and all of this is based on four hundred years of imperial rule’ (2016:19). “That presence of the past in the present, a way of acting that white people have been socialized into, that becomes natural, escaping consciousness” (2016:20). Publicist and activist Anousha Nzume asks you to see color, to acknowledge color, to see your privilege and to research your power, to create awareness about this ‘neural’ and ‘un-conscious’ position of whiteness. She writes, ‘cultural appreciation and cultural exchange with a white person means that they inevitably examine their own whiteness in the process. They will become richer in cultural knowledge and able to use their privilege for anti-racist purposes and for addressing the power structures in society’ (2017:131). Dyer is asking us to acknowledge color because, postmodern multiculturalism[7] may have genuinely opened up a space for the voices of the other, challenging the authority of the white West, but it may also simultaneously function as a side-show for white people who look on with delight at all the differences that surround them. We may be on our way to genuine hybridity, multiplicity without white hegemony, and it may be where we want to get to- but we aren’t there yet, and we won’t get there until we see whiteness, see its power, its particularity and limitedness, put it in its place and end its rule. This is why studying whiteness matters (Dyer, 1997:3/4)

Institutional life: To place the matter of whiteness in relation to being included in the institution I looked at what is the relationship between white privilege and racism and diversity in institutional life, particularly the work of Sara Ahmed, On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life (2012), was very illuminating. First of all, an institution is not the same as an institute. An institute is an organization, and an institution is a system of rules that influences our social behavior (Nzume,2017:41). Ahmed helps us get a better understanding of diversity in an institutional setting. She talks about the concept of the unconsciousness when it comes to institutionalization, “To be in this world is to be involved with things in such a way that they recede from consciousness. When things become institutional, they recede. To institutionalize x is for x to become routine or ordinary such that x becomes part of the background for those who are part of an institution” (Ahmed,2012:21). The institutional nature of diversity is often described in terms of the language of integrating or embedding diversity into the ordinary work of daily routines of an organization. Sarah Ahmed relates the institutional goals of adding diversity to the terms in which institutions set their agendas to several social constructs, which are; Market terms, diversity has a commercial value and can be used as a way not only as marketing the university but of making the university a marketplace. Part of this appeal of diversity seems to be about newness. Diversity might be promoted because it allows the university to promote itself, creating a surface or illusion of happiness. Diversity provides a positive, shiny image of the organization that allows inequalities to be concealed and thus reproduced. (Achmed, 2012). To relate diversity back to the white body Dyer argues that we should consider whiteness as well as blackness in order “to make visible what is rendered invisible when viewed at normative state of existence: the white point in space form which we tend to identify difference’ because, the media, politics and education are still in the hands of white people, still speak for white while claiming to speak for humanity. (Dyer,1997:3). Likewise, Ahmed suggest that “diversity becomes a means of constituting a “we” that is predicted on solidarity with others. Diversity pride becomes a technology for reproducing whiteness: adding color to the white face of the organization confirms the whiteness of that face” (Achmed, 2012:151)

How does this take shape for inclusive art education?: As mentioned in my introduction, education plays a crucial role in the social education of students. But then what does an inclusive art education mean when it is still in the hands of white people. This last part of my literature review speaks to art educators, managers, the curriculum but also towards the student bodies and identities which are part of this system. It indicates how art education can become an inclusive social practice, a place where diversity and inclusiveness matter. What is meant by inclusion? In attempts to define this term in relation to students and education systems, theorist from a wide range of backgrounds in the book ‘Towards an inclusive arts education’ edited by Kate Hatton, see inclusion as a complex term, developed over decades by different countries’ social and political agendas. Inclusion agendas are always measurable in terms of what can be delivered to those who are excluded. Although excluded groups and inclusive education may be difficult to define, they matter for a number of social, economic and moral reasons (Hatton, 2015). The concept of race is often applied in education debates around inclusion. Art education, however, has not embraced the term or recognized racism within its practices (Hatton 2015:5) Racism is regularly experienced by black and other people of color, but until this is understood by the white educators, managers and students in art institutions, inclusion cannot be achieved. Caroline Stevenson in ‘Towards an inclusive arts education’ refers to Irit Rogoff who connects the search for belonging to the ability to live out identities that “acknowledge language, knowledge, gender and race as modes of self-positioning” (Rogoff,2000: 14). Inclusion comes therefore with a sense of belonging, which makes me question: How do students find a sense of belonging in the art and design institution? And how does the university nurture a sense of belonging in its students, not only in relation to the art and design curriculum but also within wider cultural and creative discourses? My central aim in term of inclusive development is to provide some vocabulary and relevant theoretical framework to open up the terrain of postcolonial discourse for dialogue as a ground for ‘encounter’ across the entire student body, rather than a few. Micheal McMillan stresses the importance of a critical pedagogy of using the workshop in ‘Towards inclusive art education’ (2015) as a ‘site responsive space’ where more intuitive engagement can occur. McMillan posits that cultural diversity is still a somewhat radical concept affecting Western-European cultural hierarchies. Unless all cultural groups are considered ‘ethnic’, such hierarchies cannot be disbanded. In workshop teaching practices, McMillan suggests, the demystifying of identity can occur through disqualifying practices. He advocates taking risks with disciplinarity so that practice and theory can merge in a comprehensive and pedagogically relevant manner to meet the needs of creative work and its understandings. (2015:6) With my workshop I would like to consider the development and the impact of the nuances of whiteness within the academy in the hope of developing insights and especially opportunities to present ideas and experiences that may be a possibility for transformative practices. The result of this dialogue can take the form of both, or a written or a visual format, and includes from think pieces to illustration and everything in between.

Methodology:

For my research, I will use qualitative methodology. The qualitative researchers tend to be concerned with the interpretation of action and the representation of meanings. Qualitative data analysis is an analysis that results in the interpretation of action or representations of meanings in the researcher’s own words (Adler, Stier; Clark,2011: 388-389). By using a qualitative methodology, I will be able to gather data on lived experiences of mostly white Willem de Kooning students and not only research my own but also other student’s perspectives. All the gathered data is non-measurable and will be interpreted by my own words and analyses.

Making use of convenience sampling [8] I created a focus group interview [9] ,constructed of aluminum, ex and previous students of the Willem de Kooning academy, whom all, like me have a direct or indirect connection to the effects of institutional inclusiveness concerning students of color. All came from diverse backgrounds, five women, two Curaçaoan, one Dutch- Filipino, one Chinese, one Surinamese and myself Dutch and three males one of also Dutch and two Curaçaoan. This research comprised of two meetings discussing topics regarding; student teacher relation, student relations, the entrance gap and identity shaping within an educational institution. The reason for using a focus group interview was to obtain data through group interaction, to hear many points of view, I took the role of moderator not to primarily ask questions but instead encourage group participants to speak. The aim of this interview was to mainly gather data on the lived experiences of students of color at the Willem de Kooning academy. To test the relevancy of my research topic towards my specific research area, I suggested, together with members of my focus group, to attend the Brown Bag Lunch (BBL) meetings. The aim of the BBL meet ups is to build on creating a Critical Diversity Literate Art school. Where participants can embrace, and develop tools whereby students and teachers of all cultural and ethnic backgrounds, genders, sexualities and (dis-) abilities feel treated with equity and are supported to explore their full potential. The BBL was originally set up as part of the project WDKA makes a Difference. My aim was to bring the perspective of students of color into the BBL which was originally designed for WDKA teachers and other professionals in art education.

In preparation for my own workshop I attended a Zine making workshop by Rae Parnell organized by ‘Moving Together’ during the Activism, Art and Education Lounge at the Academy for Theater and Dance in Amsterdam. By making use of the methodology, observer as participant [10] I was able primarily be a participant while maintaining an observing role. My aim for participating in this workshop was to see how they constructed a workshop relating to a political subject, maintaining an active role for the participants but also being a workshop leader.

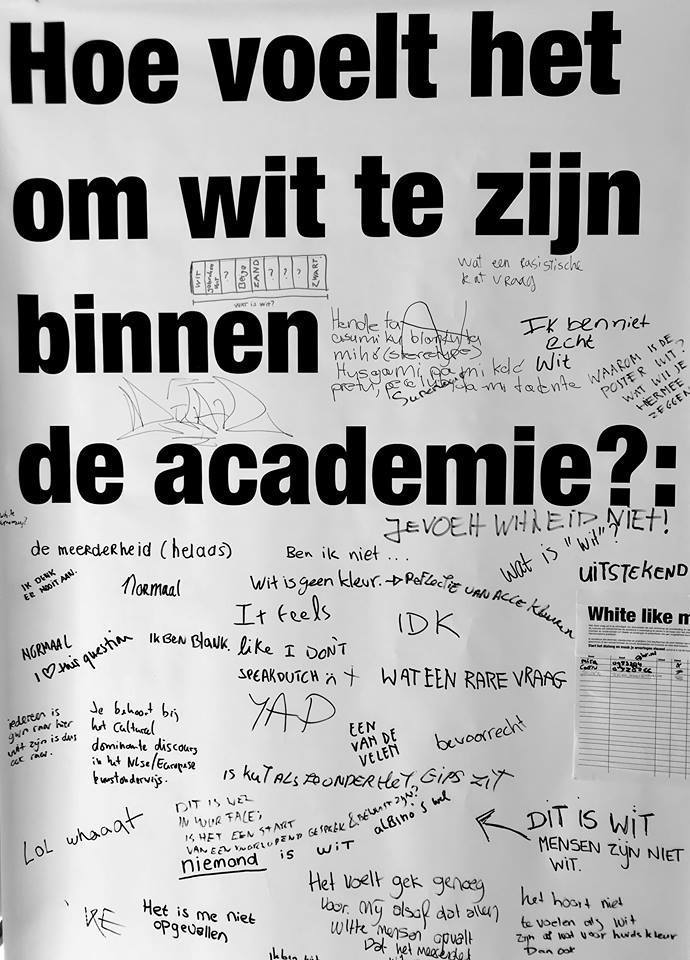

Case study [11] through workshop, the distinguishing feature of this study is its holistic approach. In this case study, I will not analyze relationships among variables but rather make sense of the case as a whole. The objective of this fieldwork is to gather data on ‘How to create a basic level of awareness and knowledge about white privilege for students attending the WDKA?’ This research comprises of 6 workshops spread over 3 days. My aim is to eventually analyze the visual and contextual data on the created awareness and knowledge about the nuances of whiteness within the academy. The exploration was designed to uncover a critical expertise in the societal complexities of whiteness in the Willem de Kooning academy. To begin my procedure, I first placed 3 posters at the Wijnhaven entrance of Willem de Kooning academy questioning: ‘What does whiteness mean to you?’, ‘When was the first time you realized you are white?’ and ‘How does it feel to be white within this academy?’ My aim with these posters was to recruit participants for my workshop about whiteness within the academy. The outcome of these participant submissions is of convenience for me as researcher.

As a second sampling option, I will use the masterclass Cultural Diversity given to second year students by Teana Boston-Mammah. I will inform the participants by email about time, date and place of the workshop. How will the workshop go? During the workshop I will have an observer as participant role [12]. The workshop will start with a group interview discussing the three earlier mentioned questions. I am aware of my own positon and how my opinions or any personal information can increase the chance of leading subjects to say what they think I want to hear and shift attention from the participants, I will have to be very conscious about this during the whole workshop. I will inform the participants that ‘I am also a student and not a teacher’, to privilege the creative nature of the workshop process by subverting the trope of the teacher as sole authority of knowledge in that space. I am using the word workshop to describe a group of people engaged in intensive discussions and activity, my aim is to eventually develop the dialogue into a making process, because I believe that the dialogue should become something tangible and that participants lived experiences should be made visible. The result of this dialogue can take the form of both, a written and a visual format. The results of the workshop will be visually analyzed developing insights and especially opportunities to present ideas and experiences that may be a possibility for transformative practices and therefore new tools on how to talk about race for art students. I am aware that my workshop will raise questions about the first-person subjective (I, me, my) and how this is rendered performative, participants can feel self-exposed and vulnerable, fearful, and therefore, in part, conflicted: welcoming of but also resistant to the process, therefore I will also position myself open and vulnerable taking a first-person position. I am aware that this discourse has been occurring prior to the self-imposed limitations of my search, and am not trying to ignore that. Rather, I attempted to make my research manageable for a subject of this size and also in line with my limitation of seeing the research through the eyes of a fresh participant in the field of art education research. Needless to say, there is much room for future research.

Findings:

With my case study, I was able to test the amount of knowledge and awareness, interest and urgency and way in which whiteness was identified by students of the WdKA. To eventually question if a space can be established where a dialogue about white privilege and its influences in art education can be given shape. I can conclude that the responses towards the three posters presented at the Wijnhaven entrance and the responses towards the actual workshop gave me two outcomes. Whereas I thought that the posters would be purely functional as a recruitment for participants, I am now able to conclude that the posters themselves became a space or tool for dialogue. I was surprised that over 100 responses were placed on the posters, because in the begin stadium of my research I encountered a lot of resistance, which will be further explained in the chapter ‘The innocence of being the ‘invisible’ norm’. My brief visual analyzation of the posters revealed several interesting themes. First of all, they show to trigger interest in the concept of whiteness, but I question the feeling urgency of the topic through the posters because the responses where places with anonymity. The outcomes towards the identification and knowledge about whiteness where frequently shared but it also provided divisions. Most responders realized their whiteness through an encounter abroad or through friends. Some acknowledged that previous school experiences or the experience of moving to Rotterdam and attending WdKA was their first encounter with BME students and therefore the realization of their whiteness. The most questions and division emerged when whiteness was connected to their feelings and their own meaning of the word. Some connect being white to the concept of privilege, and therefore to feeling guilty. Most saw themselves as normal, natural and therefore see white as non-existing. Another theme that emerged when questioning the meaning of whiteness was the connection towards tangible things or actions like ‘not being able to dance on the rhythm or wearing socks in sandals’ whereas whiteness was barely connected to systemic power. The workshop became a space for further dialogue about white privilege and its influences in art education. All ten participants, out of which two BME students, one Curaçaoan male and one Dutch- Filipino female, showed interest in the urgency of the dialogue. The workshop was mainly experienced positively, where ideas and points of views were discussed whether they were experienced as wrong or right. The space was not experienced as safe by all and some felt friction. Nevertheless, all agreed that the dialogue should continue, some gathered new vocabulary and knowledge about the concept of whiteness. The workshop brought up two major themes, that when talking about white privilege some participants really related it to their own body and lived experiences, being willing to prove towards BME students that they are not racist, but at the same time not yet being able to see how the systemic power applies to them. Wanting to see prove of their privileges but experiencing of BME students were questioned or not seen as valid. Secondly, we were able to conclude that a mandatory course about privilege would be a simulation to create awareness and knowledge for white art students, nevertheless in this course there should be special attention to the feelings of guilt and innocence.

Discussion:

In this part of the paper I will mainly talk about how I personally experienced talking about race with a focus on whiteness in several different situations taking place in the Willem de Kooning academy. Throughout this I will share my observations of patterns of behavior by whites and people of color as I have experienced them during my research. I do not aim to oversimplify the human experience. While there is no monolithic response or behavior of all white people or all people of color, and people will demonstrate their own unique behaviors at any given moment, I have observed some patterns that reflect both the existence of and responses to white culture and privilege. I believe these patterns can be instructive, and I offer them as a first insight that can might become a catalyst for change.

The innocence of being the ‘invisible’ norm:

Since I began this research, I have encountered disapproval towards my standing point of only talking about whiteness assuming it would create exclusion instead of opportunities for inclusion. Other students were questioning the existence of white privilege within our academy. Some already see our academy as diverse enough and don’t see how talking about whiteness could be a catalyst for change. I encountered a lot of ‘colorblindness’, where my acknowledgement of white, black and other people of color would by them be questioned as racist, and stereotyping, questioning whether by my acknowledgement of color it wasn’t me that was putting people in boxes, without them questioning that in which box you are positioned is sometimes already determined for you, by social constructs. As pointed out earlier by Dyer, this unawareness of color by white people is the most powerful positon. I can understand the resistance a group of people might have to examining something they don’t consciously know exists. But when it is given a name and examples are pointed out, its presence is undeniable. Thus begins the journey to see, deconstruct, and potentially transform white culture. I became frustrated with the realization that people did not feel comfortable with the language. There is no comfortable vocabulary available in the Dutch context to talk about whiteness, so I argue that “the end of racism will be possible only after we find a way to see Whiteness, to name it to examine it”. The ride will be rough, but after your eyes have been opened, there is no point in standing still. This stand implies taking responsibility for your unwilling participation in these practices and beginning a new life committed to the goal of achieving real racial equality. This realization made me decide to just design the three posters questioning whiteness within our academy. Being aware that some would find them injurious, too direct or wouldn’t understand my positioning, it felt I had to step out there and just start talking about it.

In my experience, it also became the place of greatest resistance, for the following reasons. The first is that I realized that the exposure of whiteness is a new concept within the academy and that some people don’t know how to respond if their ethnicity is questioned, when something so unconscious might be brought to your consciousness, as mentioned by Wekker as escaping consciousness. Example: Shortly after placing my poster I was approached by the Hogeschool Rotterdam ‘Facility and information technology service’, after first encountering some disapproving faces by the receptionists I was asked to speak to the head of the service. He questioned my intentions with the posters, as they were placed at the entrance of the academy. Being afraid that my questions about whiteness could be assaulting and hate calling. After explaining that I wasn’t responsible for the answers given on the questions and that the given answers would reflect the lived experiences of our community he agreed to keeping them, under the condition that they could be removed as soon as he thought they started provoking violence. Secondly, culture lurks in every nook and cranny of organizational life, which now must be intentionally examined, considered, and negotiated. This means that many only examined themselves as an individual, disconnecting themselves from organizational life, and therefore disconnected to the systematical power, or as Wekker would say the ‘cultural archive’, embedded in whiteness. My posters gave great insight in how this is constructed in the community of WdKA: Where some were shocking, like the swastika or some people tried to be funny about it with responses like ‘whiteness means having to use more self-tanner’ or ‘wearing socks in sandals’, others were very positive acknowledging ‘unconscious privilege’ or ‘Belonging to the cultural dominant discourse in the Dutch/European art education’ Further, an honest look at white privilege might lead to hard truths about the foundation itself, foundation structures often embody dominant white western culture and white privilege. By definition, this is normalized and difficult to see, prompting resistance and defensiveness about dissecting the core of the educational institute and therefore themselves.

The emotional labor:

Since personal experiences about race come packed with emotions including anger, frustration, hurt, and fear, it is hard to keep them in check when you are asked to examine something so ‘normal’. Because these feelings do not always feel good, some white students acknowledged the feeling of “failures” during the workshop and therefore acknowledge the process and reasons to abandon or restrict it, rather than accepting them as necessary and indicative of real change. I have observed white students shutting down because of discomfort with the rawness of emotions, fear of disclosing personal experiences that may suggest they have bias or racist thoughts, or the assumption that talking about white privilege means they are “bad” individuals instead of seeing privilege in the context of the system in which we all participate. I can always use myself as an example, because during my minor ‘Culture diversity’, I had to acknowledge and question my dis-comfort, also other white students acknowledged this feeling of guilt and not knowing how to deal with the feelings of dis-comfort during my workshop. Questioning: “Am I now guilty?”, “What to say at these moments?”, “I’m not the victim here right?” and “How to deal with these subjects?”. These response to emotions is not a fault, but rather a manifestation of how the system is set up for people who are privileged in it. The default setting is for the structure to be invisible, to be institutionalized and therefore by Achmed called as routine and part of the background. For some, this is the first time they are realizing they have a white identity, learning about a system of racism rather than seeing racism as individual acts of hate, or even having an intense conversation on race. It may be the first time they are considering how the system is set up and may have furthered their career, performance appraisals, and quality of life. As a result of all this newness, plus discomfort with the emotions arising from within themselves, they often will advocate for even more strict boundaries around personal sharing and emotion when it gets too heated for their comfort. On the other hand, many people of color talk about their anticipation of having an opportunity to share one’s truth in a facilitated space and the potential that these discussions may result in institutional changes. In my observation, people of color are typically taking the lead in sharing personal experiences since they are more fluent in the impact of inequality. They also might feel hesitation, since people of color are typically looked to for sharing their personal stories and lessons yet are covertly or overtly asked to keep their emotions in check. Some people of color have expressed fear that they will face harsh consequences for speaking truth as a further marginalization, loss of credibility, or something worse. An example of this occurred when at the end of my workshop I questioned the participants about feeling safe, where one BME student answered: “At one point I wasn’t feeling comfortable, but decided to stay. Because I felt that if I can’t prove something I’ll be seen as wrong, weak or not in an unbiased position.” Acknowledging feeling hopeful but frustrated at the same time. I believe that the dialogue must be open and receptive and make space for conflict and emotion. Without this, the process could unintentionally repeat the experience many people of color have throughout their lives, that is, efforts are made to address racial inequity, but when the conversation gets heated or uncomfortable for white students the group retreats, which in returns ads anxiety for people of color, who may be unlikely to risk participating in such a process again. Because as pointed out by Dyer postmodern multiculturalism may have opened up a space for voices but this shouldn’t become a side show for white people to look at all the differences that surround them. I am aware that my process likely will increase conflict, at least in the short term, but as issues of concern become more visible, I hope that people of all races gain language and tools for talking about them, and the process itself invites more open communication. Therefore, I believe that limiting the choice of participation in courses like ‘Cultural diversity’ and creating a mandatory course to learn ‘how to talk about race for art students’ because also Hatton acknowledges that art education has not yet embraced the term race or recognized racism in their practices therefore doing this could function as a possibility for transformative practices.

Can we only focus on white privilege?:

This last part is constructed around the question one white participant of my workshop was taking home: “The question whether we as white people are able to tackle the dialogue about whiteness without the counterpart of blackness?” I will try to construct this question with three points in which I’m taking lived experiences of BME students regarding; student teacher relation, student relations and identity shaping within an educational institution as a leading point. First during the workshop it for me became clear that an overview of statistics showing racial disparities in different sectors would be the only way some white participants could be convinced of their advantages of being white over people of color. While these might validate the experience of people of color, they also can leave them feeling detached from their personal and lived experiences of racial oppression. In this way, this method can privilege the convincing of white students over the comforting of students of color. This also became clear during the workshop when one BME student confronted a white student “Why do you really assume that white privilege is so connected with the actions you do, such as eating a cheese sandwich?", after which he asked for a concrete example of an advantage he has as a white person to a non-white person. The second is when the dialogue mainly emphasizes structural outcomes to the exclusion of personal bias, individual racism, and earlier mentioned sense of belonging. As a black student acknowledged “Knowing that your body will always be bound to a certain stereotype. (it’s frustrating) having to prove as an individual that you are an exception, so that they cannot claim that you represent ‘all black people’, the position of a stereotype”. Which leaves students of color feeling that no one is taking responsibility for the persistent pain and consistently inequitable outcomes and experience being generated by structural racism. In this way, as pointed out by Achmed, the organization as a whole may make progress in its understanding of structural racism, its commitment to racial equity, and diversity might provide a shiny image, at the same time that students of color may feel more isolated in their daily experience of racism within the institute, that allows inequalities to be concealed and following Achmed her theory, reproduced. Example: If we as students want to provoke change they will still have to give us the space and opportunity to do it, which stands in relation to power balance,” I’m not going to make something from Curacao because I don’t think the teacher is going to like it, but if you make it, you can make something a 100 times better because of the affiliation, and the teacher is able to learn something as well and guide you better in your personal development”. The third way this approach can privilege white students while re-marginalizing students of color is that the necessary focus on white culture and privilege, which I still maintain is critical for racial equity to be effective, means that the white experience takes center stage in the change process. Students of color, who often have to accommodate, adapt, and assimilate in countless ways in order to gain entry and reaching the norm in white cultural institutions, which as Dyer says might speak for humanity but are still in the hands of White people. These MBE understandably might grow weary of bearing witness to white students discovering and grappling with their white privilege. Where one BME student questions: ‘if she still wants to invest to have more dialogues in school for the white majority people whom then hopefully will be aware of their white privilege. She encounters not being that interested anymore in people whom don’t want to learn and invest in themselves.’ As observed on the three posters this process can include everything from denial to angry pushback from white students, jockeying to position oneself as the exception to the rule, or paralyzing white guilt and shame. Meanwhile, students of color are asked to be patient and graciously share their stories, as this is part of the necessary process of white students becoming ‘allies’ in the struggle for inclusiveness. The question is whom should get empowered? And how can our stories be connected? To more easily and faster be able to connect with another to share these stories.

Conclusion:

With my central aim in terms of inclusive development to provide some vocabulary and create a theoretical framework to open up the terrain of postcolonial discourse around whiteness for dialogue across the entire student body, I hope to have developed insights and especially opportunities to present ideas and experiences that may be a possibility for transformative practice. I still feel that is it important that “we” get used to thinking about whiteness a bit more often, and therefore inevitably examine our own whiteness in the process of becoming more inclusive in art education. Where earlier pointed out by Anousha Nzume, “we” will become richer in cultural knowledge and will be able to use our privilege for anti-racist propose and for addressing the power structure in society. But after encountering, resistance, guilt, the feeling of failure, unconsciousness and the un-comfortableness of white students, I question “How to talk about race for white art students?” My future aim is to challenge, and expose whiteness, to continuously breach this concept that now feels like a taboo. I don’t have the answer for the ‘how’ but I know that the journey to see, deconstruct, and potentially transform white culture will be rough, but my eyes have been opened and for me there is no point in standing still, therefore, I will present my own journey as a starting point of the dialogue. I believe that this dialogue about race shouldn’t be a choice as it is relevant to understand your life experiences and identity. I believe that the dialogue must be open and receptive and make space for conflict and emotion so that issues of concern become more visible. I hope that people of all races gain language and tools for dialogue and therefore invites more open communication about these sensitive subjects. I hope that this study can provoke work in the direction of a more just society, where art students will engage the world not only to beautify it, but also to deconstruct its systems of oppression.

Footnotes 1: The Inspectorate of Education, the Netherlands: p6, the-state-of-education-in-the-netherlands-2014-2015.pdf, 2016 2: Demographically in the cities this is starting to change; see ‘research area’ for demographics, however the power of discourse around whiteness in the Dutch context is definitely white. 3: See below in ‘Whiteness’ for an explanation of this term. 4: WDKA Makes a difference: The entrance gab, Teanna Boston-Mammah, 2016:8 keynote 12 5: bevolkingsmonitor+januari+2018.pdf, https://rotterdam.buurtmonitor.nl/news/Bevolkingsmonitor-januari-2018/58, last enterd:20-05-18 6: https://rotterdam.incijfers.nl/jive?cat_open=Beleidsthema%27s/Demografie, last entered:20-05-18 7: Dyer uses the term postcolonial multiculturalism in terms of living in a world of multiple identities, of hybridity, of decentredness and fragmentation. The old illusory unified identities of class, gender, race, sexuality are breaking up; someone may be black and gay and middle class and female. 8: Adler, Stier; Clark,2011:119, convenience sample: A group of elements that are readily accessible to the researcher. 9: Adler, Stier; Clark,2011:259, focus group interview: A type of group interview where participants converse with each other and have minimal interaction with a moderator. 10: Adler, Stier; Clark,2011:289, participant as observer: being primarily a participant while admitting an observer role. 11: Adler, Stier; Clark,2011:172, case study: a research strategy that focusses on one case (an individual, a group, an organization and so on) within its social context at one point in time, even if that one time spans months or years. 12: Adler, Stier; Clark,2011:289, observer as participant: being primarily a self-professed observer, while occasionally participating in the situation

Bibliography

Adler, Emily Stier; Clark, Roger. An Invitation to Social Research: How It’s Done, 2011

Adusei-Poku, Nana .Catch me if you can!, 2015, http://www.internationaleonline.org/research/decolonising_practices/38_catch_me_if_you_can (last entered on: 05-03-2018)

Adusei-Poku, Nana. The research project: Challenging exclusion,2016, http://wdkamakesadifference.com/about/the-research-project/ (last entered on: 27-03-2018)

Ahmed, Sara. On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life, 2012

Boston-Mammah T., Adusei-Poku N., Moukhtar E., Van Heemst J. ,WDKA Makes a difference reader, 2017, Rotterdam http://wdkamakesadifference.com / http://wdkamakesadifference.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/WdKaMakesADifference-Reader2017.pdf (last entered on: 05-03-2018)

Dyer, Richard. White, 1997

Hatton, Kate. Towards an inclusive arts education, 2015

Nzume, Anousha. Hallo Witte mensen, 2017

Wekker, Gloria. White innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and Race, 2016Links

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.