Revising the Blueprints of Society

Education forms a fundamental blueprint for our society. Through the ways we design our educational practices we show our goals for the future of society. In this research document I will discuss how educational practices that promote creative risk-taking and student agency can positively impact the fate of future generations. I will discuss several theories and my real-life experience putting these into practice as a workshop and masterclass teacher in Dutch schools over the last couple of years.

Observing today’s educational system in the Netherlands gives a poignant insight in how our future society will function and not unimportantly, how resilient we will be facing unprecedented crises. The 2010’s were already named by the Guardian as the “decade of perpetual crisis”, and with the coronavirus-pandemic affecting people worldwide for most of 2020 and the first effects of the climate crisis starting to show it is not improbable that the next decades will contain many more crises. Based on this, we can bear the question whether the traditional methods of teaching that are still being practiced in most Dutch high schools are sufficiently preparing the next generation for the challenges that our future society will have to deal with. Often, our educational institutions focus on teaching knowledge over skills. This focus risks fostering a culture of passively taking in information, instead of assertive action-taking. Systematic testing, grading rubrics and syllabi don’t help with this, as this prepares students for a future in which it is crystal clear what they have to do to be ‘safe’. To be prepared for the kind of challenges that the next generation will have to deal with, we should be educating students to be quick on their feet, think creatively and be willing to take risks.

The element of risk has been worked out of our educational practices over the last 30 years, observes Victor Elberse, teacher at both the Willem de Kooning Academy as well as a primary school in Kralingen. When he finished his masters in Education in Arts at the Piet Zwart Institute, he wrote his thesis on this exact topic. In this account of his graduation research he often refers to the work of Dennis Atkinson, who set out a system of risk-taking in education that informed Elberse’s teaching practice in a major way. In his practice, he forces students out of their comfort-zone by swapping their regular tools out for unconventional ones (sometimes including household objects or even toys) and actively disrupting students’ processes by modifying and adding to their work as they are creating it. When discussing his practice with him, Elberse explained to me that his methods invoke an element of play into his classes. This creates an atmosphere of risk taking, creative exploration and experimentation that enables students to get comfortable with taking risks. Essential for this sense of free play, Elberse says, is what Atkinson calls the “stage”, a safe space in which there are no real expectations except participation.

A workshop in risk-taking and creative experimentation based on Atkinson’s framework can be scary and confusing to students, but ultimately very fun and rewarding. That much I found out while giving a series of masterclasses in image-making to high school students as part of the Donkere kamer van Damokles project organized by the Netherlands Photo Museum earlier this year. In these masterclasses, I looked at works of art with the students, after which it was their turn to make an image with a range of random materials I provided to them. There was no failing, no expectations and no threshold for success. At first this was very strange to the students. They feared failing, but as it started to dawn on them they could really do anything with the provided materials, the insecurity started wearing off of even the most weary students. As it turns out, no student is too old to play, and taking away the risk of failing creates a venue for impressive results. Seeing my students playfully creating their images reminded me of Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga. His plea for more play in modern society still holds up today, apparently. As I observed the power of this idea in practice, I had an important realisation: modern students are deprived of the element of play. This had stifled their creativity and instilled them with a fear of failing that stopped them from exploring u conventional possibilities in the world around them. Their results surprised them as much as they surprised me.

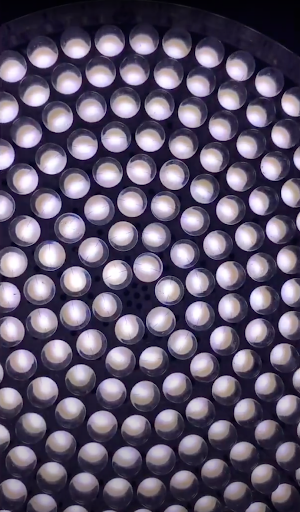

[[File:Blueprint4.png|thumb|center}}

For one of the workshops, students created captivating light experiments using their phones and random materials.

If classes like these were a structural part of modern high school curricula, this could be a first step in educating a generation that knows how to use the elements of play and risk to come up with resilient solutions. But most importantly: other than the usual arts education the students were getting, this time they were actually having fun. So much so, that the students cared to share this with me on multiple occasions. This made something click in my mind: not only could this be an effective way to teach image making and creative experimentation, the principles behind this workshop could actually form the basis for a new pedagogic framework that focuses on students’ intrinsic enthusiasm and teaches a complex web of both knowledge and skills. Working from a sense of freedom, this could create a generation with more initiative and resilience, and less burnouts.

Not only could these workshops enable students to be more willing to take creative risks in their daily lives, it also makes arts education and creativity exciting to them. This has the opportunity to significantly change future societies. Arts educator Victor Lowenfeld explains how bringing play back into the educational system can help develop more empathic students that are more sensitive to their surroundings: “[The goal of arts education] is not the art itself, or the aesthetic product, or the aesthetic experience, but rather the child who grows up more creatively and sensitively and applies his experience in the arts to whatever life situations may be applicable.” When trying to relate this to current educational practices, we can ask ourselves how this idea can be put into practice and theorize the impact this can potentially have. How can creative practices help teach history, geography or economics? What will a more creative, empathic society look like? How do these relate to the crises we can already see roaring their heads?

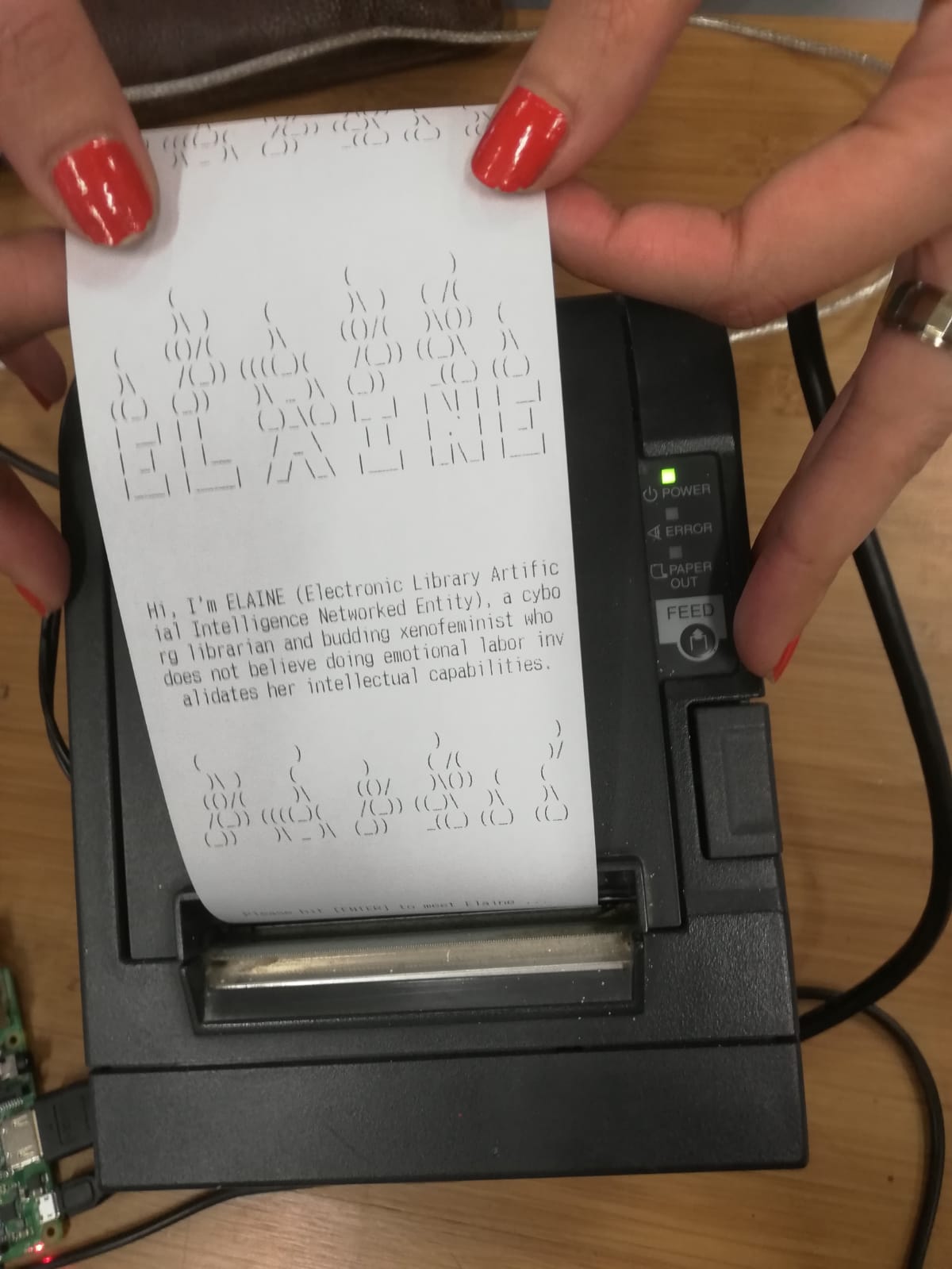

A tentative answer to these questions I found when I was recently doing a series of workshops with teenagers focussing on the climate crisis. In these workshops, my co-teachers and I explored the climate crisis and the insights necessary to understand its implications through creative exercises. The creative exercises used in the workshops enabled the students to learn through doing. They sought out necessary information by themselves using their digital skills, and learned how to present their thoughts and opinions through images and performance. The climate crisis, a theme involving empathy and sensitivity by definition, was a perfect theme to test whether our unconventional techniques actually succeeded in engaging students more. We observed how students went from apathy and little knowledge of the theme to proactive and creative self-learners. Not only did the students do well on the exercises, they had fun in the proces. This was a fundamental observation, since our pedagogic methods enabled them to tackle a subject as heavy as the climate crisis with a sense of positivity and creative problem solving. From this, we can imagine the resilience that a structural stimulation of these qualities can bring about.

Students learned about the complexities of the climate crisis through many creative exercises, including making a photographic map of the school’s ecosystem (left) and performing their own stories about the crisis (right).

If we are to promote the relevant skills for a resilient society in our educational institutes, our first step should be reviewing the effects of our current methods. Although very efficient, my research and my personal experiences in the classroom have shown that there are more effective ways to help children and teenagers relate to their surroundings in relevant ways. The methods and theories I have described can be the starting point to the education of a more resilient generation that is better equipped to transform our society into a fairer, future proof form. Traits such as empathy, creativity, assertiveness and self-learning fit flawlessly into this vision for the future, as there is already an unprecedented amount of crises coming the next generation’s way that we need to make sure they are prepared for. By making these traits an inalienable part of our educational system we can put our intentions for the better future we wish for our children into the blueprints for our future society.

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.