Business you can't wait for

Contents

The wikipage input value is empty (e.g. SomeProperty::, [[]]) and therefore it cannot be used as a name or as part of a query condition.

Authors: Ana Džokić and Marc Neelen

The post-2008 era has caused an avalanche of changes in the work of designers. This has left a considerable group -temporarily or permanently- with an evaporated or seemingly redundant conventional practice. In architecture or product design temporarily (decreasing demand), but in spatial design it is probably irreversible, because of the dismantling of entire planning institutions. In recent years, a range of designers thus has seen themselves ending up in a strange position. In order to survive, part of this group has employed its "creative talent" in a flexible way, to tap into new markets. For example, in cases where the ramifications of radical changes of a failing market or government would lead to too explosive situations in certain urban areas, resembling the risk of Detroit-like conditions. Or in cases where corporations threatened to nail down houses due to insufficient maintenance budgets. Or in entirely renovated shopping areas, now desolated because new retailers were not in for a risky start in times of crisis.

Stretching some efforts, designers are here still able to rescue things nicely - and at a comparatively friendly investment budget. In Rotterdam, the Zwaanshals has been pulled out of the doldrums through the concept of a "food, fashion and design district" and the energy of many design pioneers. This focus is of course not infinite; either because the market revives (we can do our old tricks again, though chances are not considered very likely) or because the things once rescued with creative patchwork may require a more systematic solution and this kind of talent is no longer the approach requested.

Eventually, the design field will need to reinvent itself considerably. It is therefore more complicated for the starters and even for upcoming designers. How can they prepare for their future field of practice – a reality that is much more grim than the brochures from academies and universities and design glossies would like us to believe. And how do we seduce them not to leave the design discipline behind as a risky minefield and search for a more sustainable and resistant practice?

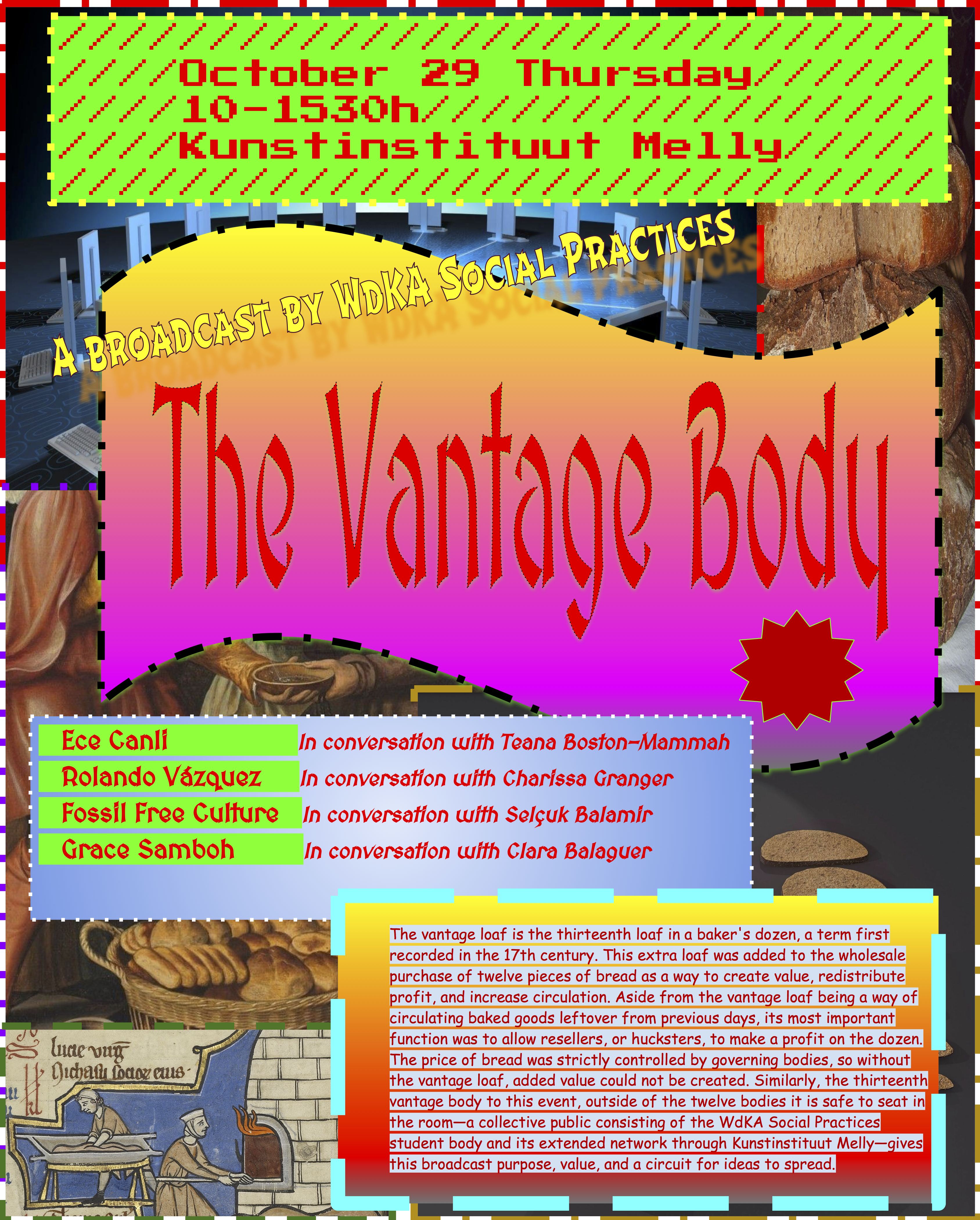

While educational institutions have been able to restrict the prospect of a "withered" career landscape by massively focusing on those design areas that some years back were considered less serious "peripheries" of the design field (temporary use of open spaces and buildings, for example) - and now increasingly as its core -, the need for redefining the profession has become evident. The rise of 'design thinking' and the 'social design' departments of various academies reveal what is at stake: other ways of designing, and for different purposes. This does not only concern the profession, but also the way we work, as a design community. Even a lifestyle designer is nowadays expected to express a "nearly activist attitude in a changing world full of challenges". Because the earlier answer to how and through which means we could earn our existence currently seems barely relevant for future designers. The fact that students and teachers now focus on the role of "creative disciplines in the development of new business models" (as in the WdKA symposium and master classes 'Redesigning Business', November 2014) is not only relevant, but also urgent for those upcoming "creative entrepreneurs".

It is however, far from easy to distill concrete results from these initiatives. It is therefore important to surpass the hip but often rather naive or not particularly robust business plans, and to realize that precisely the ability to bring such proposals to reality is at the core of what makes or breaks all the plans in question. If you yourself won't even to stand for it, then it seems very appropriate to expect this from others. Exactly this attitude of "taking a stand" is beginning to sign off as an important parameter for attributing new meaning and momentum to creative disciplines. Not only devise plans, but also put them into effect. And if needed, take this stand for a few years, because you find it important. Then the plan suddenly needs to have been thoroughly worked out, and you need to believe in it and be convinced of its importance. In that case, it usually transcends the scope of an individual designer: you have to take a stand as a group, or preferably, as a community.

Also for our selves (no longer young promising talents anymore) this begins to manifest itself. In a group of moderately obstinate designers and cultural practitioners, we have started to address the things we find important, one by one. Such as the lack of space and programs for an idiosyncratic "maker culture." While in the city around us the opportunities to encounter intriguing, pioneering culture are fading away or embody a stopgap padding to vacancy, we want to create space to destine and develop our future together with large group of creators. Not temporary, but lasting. To achieve this, we go back –or rather, forward - to the cooperative form of entrepreneurship. For such forms of cooperation have been the basis of unruly, emancipating and innovative initiatives, in times when groups formed who - out of dissatisfaction with the state of things- took the future into their own hands and initiated projects that could not be pulled off by someone alone. But at the same time we are too stubborn to let us be told by someone (i.e. management); we will manage ourselves, amongst ourselves. An attempt to do so could emerge from a recent bid on a large but neglected movie house in Rotterdam. The aim is to add a cultural initiative to the city, driven and programmed by makers: from design to theater, from debate to film, and more. Cooperative, of course.

Redesigning business (or actually redesigning practice) is in this case not so much the result of ingenious creative talent, or a smart business sense, but of attitude. It is about a "business" that we face together, of which we bear the risk together. Its profit in the first place is to see a culture and city that we want to see around us. But also a model that is economically sustainable enough to eventually support independence.

We believe that upcoming designers (those promising young ones) could also get to work from this perspective. Work together, be realistic about your survival strategy, and get started with things you - not just alone, but with more – no longer wish to wait for. Because that energy from your "creative power" alone, well, that will wear out again soon as well. Rather do things that you believe in, or join unruly ideas you want to be a part of – that will be your profit.

Ana Džokić and Marc Neelen form STEALTH.unlimited together.Links

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.