Embed Yourself

Author: Jessica Hammarlund Bergmann

em⋅bed⋅ded /imbedid/ adjective 1 inserted as an integral part of a surrounding whole • confused by the embedded Latin quotations • an embedded subordinate clause. 2 enclosed firmly in a surrounding mass • found pebbles embedded in the silt • stone containing many embedded fossils • peach and plum seeds embedded in a sweet edible pulp

WoordBook.com

When do we use the term 'embedded'?

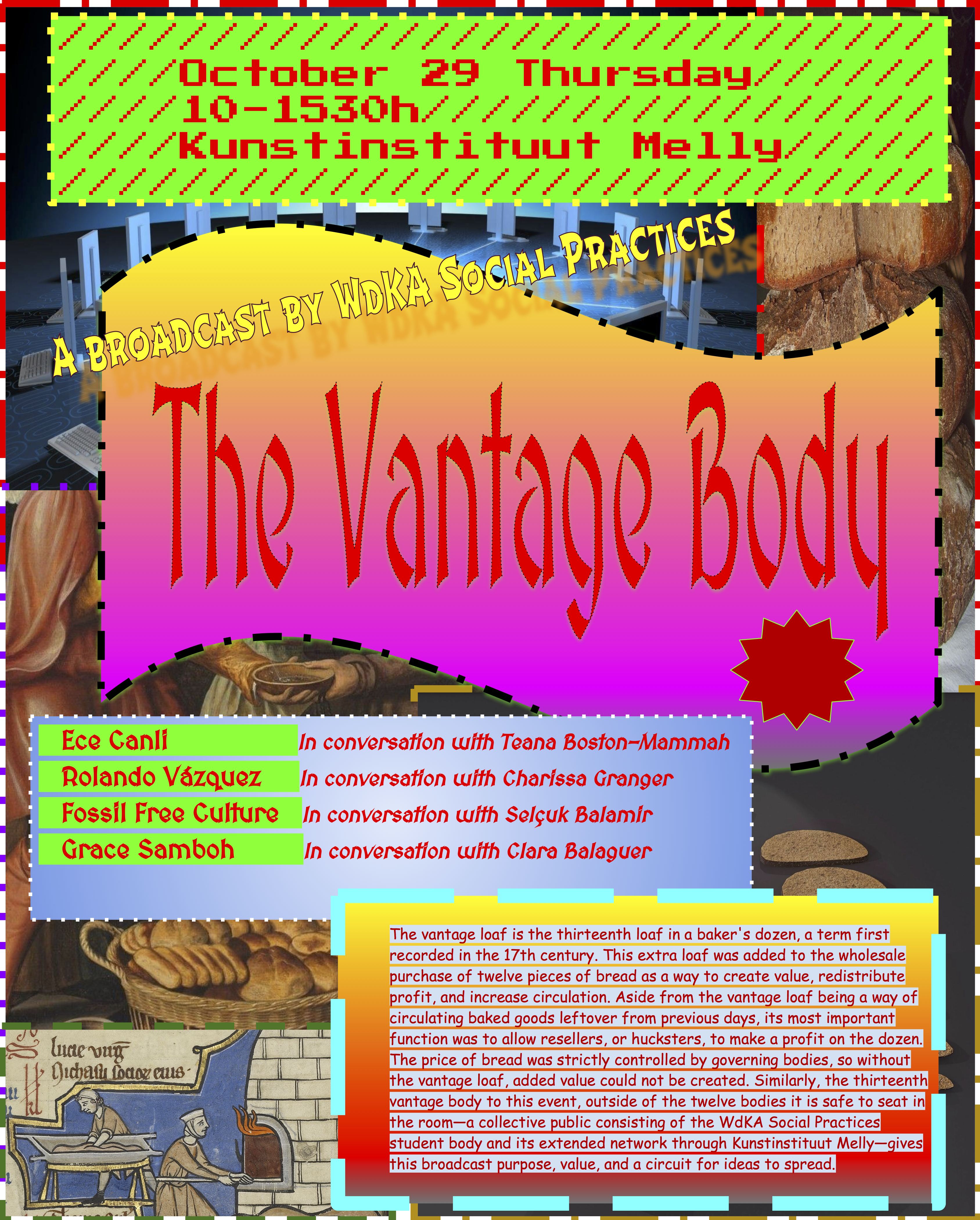

Is being 'embedded' related to the amount of time we spend working on location, immersing ourselves in a foreign context – or is it about a specific intensity of attention? Until now, the term 'embedded' was primarily related to journalists traveling in an embedded way with the military, most famously in the Gulf War. Becoming 'embedded' gave journalists a possibility to get closer to the battlefield. However, it also creates a relationship of dependency, which has been a topic of debate in the media. Anthropologists have also been known to conduct research by living on location, which has raised a debate about 'pollution': by inserting yourself in a context, you change the context and therefore 'pollute' the research. Both journalists and anthropologists are expected to keep a professional distance to their story or research topic in order to assume an 'objective' point of view. We are different. An artist or designer who works in an embedded way can position her/himself in a much more subjective way. As opposed to a journalist, an anthropologist or even a 'pure' scientist, artists (in order to realise their project/artwork) are often aiming for a much larger and more differentiated visibility or impact. Within the Social Practices graduation profile, we teach students to interact and to change; be it the situation, or the perspective on the situation, temporarily or permanently. It is precisely this interaction that is interesting for everyone who works in the field of art and societal issues. We want to teach students ways of studying the contexts, to enable them to analyse and interpret – and to use their artistic skills to make a creative translation or reframing of that context. In seeking a stronger interaction with society, we need to develop other tools and working methods than the traditional ones taught at art academies. What we at the WdKA call Social Practices is far removed from the isolation and independence of the artist's studio attic. When working in an embedded way, you encounter ungovernable contexts with unpredictable dynamics: residents who won't open the door, who don't stick to agreements, who don't respond the way you expected, who suddenly become angry, fearful or extremely intimate – in short: when working in an embedded way, you become part of something you cannot control – and our challenge at the WdKA is to teach students to creatively position themselves in this chaos.

Four didactic methods for students

Working in an embedded way can teach the students valuable lessons. About curiosity, empathy and courage. About meeting the 'other'. My interest and experience in embedded research stems from my work with the artists' collective Pink Pony Express (PPE) and from my teaching during the past three semesters at the WdKA's Social Practices (Cultural Diversity). From this experience, I have distilled a number of important aspects, which, translated into didactic methods, can have a great impact on the artistic and personal development of any art academy student who looks outward for inspiration and challenges. I will discuss some of these aspects below:

Living with the natives getting close and professional

Living and working long-term in the context that you are investigating, is an intense way of working. The 'research organ' is active 24/7 and everything you experience has the potential to turn into interesting phenomena: the way the street looks (# Drawing on Farnsworth), or the fact that everyone is wearing shoes that are too big (# Okina Kutsu). Even garbage on the street can be the beginning of a project (# Supernatural). (See illustrations). To conduct this particular kind of artistic research, you have to leave all preconceived ideas behind and continuously adapt to changing circumstances. Embedded research invites you to get very close to people and to explore foreign environments. It is therefore not only a rich professional working method, but working in an embedded way almost always raises fundamental questions. Questions about giving and receiving; when you insert yourself in a social context, you build personal relations of trust. Relations that will not develop if you are not prepared to give (at least a part) of yourself. Then the questions arise: can you get close to people and still keep your independence and integrity as an artist? Are you obliged to maintain those relations when your project is finished? With the PPE we used to call this 'giving back to Rome', arising from a discussion we often had in Detroit. When you work in Rome, with all its splendour and history, you don't consider what you can give back to the city. But working in the dilapidated neighbourhoods of Detroit, this topic was at the centre of the discussions between the visiting artists and the residents. Detroit at that time was a 'ruin hype'; many artists and architects settled temporarily in the city to work on or realise a wide variety of projects. Just like their stay in the city, many of these projects were also 'only' temporary. So does that mean that we exploited the city, or did all these activities also contribute to a permanent change? Does 'temporary' mean 'without value'? Maintaining your integrity as an artist sometimes means that you will develop a project that will piss people off. People who have let you into their homes, people who have confided in you. In the midst of all these fundamental questions, you as an artist will have to find your way and decide how you want to position yourself (personally as well as professionally) – making embedded research an ideal method for art education.

The group the gift of interdisciplinarity

At the PPE we had four different designers from three different disciplines: two graphic designers, an exhibit designer and an urban planner. We also had three nationalities: Dutch, American and Swedish. This meant that each step in the process was viewed and enriched from multiple angles and specialisations. Interdisciplinarity also takes place in the minor at the WdKA, because students come from different directions, and potentially also from a variety of nationalities. Since conducting embedded research within Social Practices is very time-consuming and demands various specific qualities (social interaction, strategy, analytical and intuitive skills), working in interdisciplinary groups can stimulate the individual student and widen their horizon.

The social worker working in an embedded way doesn't mean to always play nice

Most students begin the Social Practices graduation profile thinking they should always be helping someone, that social design is all about getting people together, organising neighbourhood barbecues or platforms for elderly citizens. And sometimes it is. But in my view, Social Practices are also about asking questions, starting the debate, changing perceptions. And sometimes the only way to really get people's attention is not to play nice, but rather to provoke, to move the public out of their comfort zone. As artists we are not social workers, and the aim within the Social Practices graduation profile is still to develop the artistic intuition and language of the individual student, to develop the capacity to artistically respond to societal issues and apply these in projects, to follow your own personal intuition or fascination – to find that fire and to keep it burning. 'What I see in all the talented artists who make beautiful, good projects, is the ability to listen well' says Steve Elbers from Stichting Doen. 'It's a quest with a lot of trial and error, so you should be prepared to engage in dialogue and at the same time know who you are as an artist and how you want to position yourself – so that they do not run away with you. It is so much more than organizing fun activities and hold someone's hand. The inherent struggle between the artist and the context is interesting. How the artist interprets and translates the given situation in a way that has an impact.'

The power of the image crossing all borders

My work with the PPE evolved around the power of an image in circumstances of friction and societal tension. The PPE has always worked on locations in transition. These transitions (economic or political crises, social exclusion or massive urban transformations) are often the cause of friction between citizens and their governments. Using the image as medium enabled us to offer new perspectives on the situation, without having to choose sides in the conflict. Everyone can relate to an image – no matter what your cultural background, education or religion happens to be. Although an image has multiple layers, it has the power to transcend all these borders and the stronger the image is, the stronger the emotion or reaction to it. With the PPE we used image in the broadest sense of the word; sometimes it was an installation, sometimes an app (Raduga), sometimes an election process (Golden Rock).

Conclusion

Fulya Erdemci, the former director at SKOR (Stichting Kunst Openbare Ruimte) once told me what according to her made an artwork in a public space successful: 'Good work always has multiple layers, multiple meanings. In this way the work can tap into a wide variety of different people, and mean something to them all.' You can only add these layers after understanding (having experiences with) the multiple layers of a context. So: go and embed yourself.Links

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.