History: Critically Revised

Contents

The wikipage input value is empty (e.g. SomeProperty::, [[]]) and therefore it cannot be used as a name or as part of a query condition.

“Becoming is better than being” (2006, p. 16) Carol Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success

The initial inspiration for this project came from the essay I had written during the Minor Cultural Diversity at the WdKA. In this essay called “How education is used to institute indoctrination,” I - a Dutch, straight, cisgender, white, male brought up in a small catholic community with a mother, father and a younger brother where I was always led to believe that this was the normative idea of what life looks like - want to analyze the Dutch curriculum and uncover the way the content of this curriculum is being used as a vehicle to form the national identity and cultural archive.1 When I was young I have always been in a very centralized position. This was something I did not consciously live with. When I was 10-11 I remember at the beginning of my school year we had a new student that was coming into our class. He was an Afghan refugee who had fled to the Netherlands with his parents, little sister and little brother. Very quickly we became friends. We played during recess in school and met up after school at either his house or my house. Back then I had never learned anything about Afghan culture apart from the things I had heard on the news about the war. I remember going to his house and meeting his parents who did not speak Dutch as well as their son spoke it. They were so warm and inviting and I was invited to join them for dinner and ate things I never ate before. The most important thing that always stuck with me was how other classmates would behave towards him and would bully him for being different. I never understood why they did this up to a certain level. This awkwardness and struggle in interacting with other cultures is something I thought derives from the lack of information and different viewpoints. This was before I had read the work of Gloria Wekker. Something that shows Dutch people are being taught a very mono-ethnic or mono-cultural idea of the Netherlands. I recognized this in my classmates acting towards my Afghan friend. The Dutch historical curriculum did not tell me anything about Afghanistan, for my classmates, it was not part of Dutch history and therefore “not-Dutch”. This ties into my research question where I ask how can making changes to the Dutch historical curriculum change the Netherlands and the way they now institute indoctrination by showing one perspective on Dutch history. In doing this creating a Mono-Cultural society.

I felt a sense of urgency to share this knowledge and these topics and decided to make it into a small pocket size book I could share with the people around me. I also showed this to my parents and asked them to read it. In my enthusiasm, I thought they would understand my point of view on this topic and would agree with me. However, this was not the case. They did not understand the urgency and also did not agree with some of the arguments I make in the essay. To understand this phenomenon of ‘not understanding the urgency’ in my essay and me ‘not understanding’ why they could not see what I saw, I decided to start researching the psychological aspect of what could cause this reaction. To do so I decided to start reading work on how the mind works, how people form their opinions, and why they hold on to them in the face of evidence to the contrary.

This led me to examine theories and related concepts that actively work towards developing a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006). I did this by looking at the work of heuristics (Tversky, Kahneman, 1974), NFCC ( Need For Cognitive Closure) and seizing and freezing (Kruglanski, Webster, Klein, 1993) as a way to develop my understanding of ‘not understanding’. I will be using the knowledge I gained in exploring the above scholars to create my practice project. Because the canon on Dutch history has not changed fundamentally in over 20 years I want to effectively design and implement a game for primary and secondary education. In order to stop this ongoing process of purposely withholding historical information to the majority of the students in primary and secondary education, I want to address this group first with the opportunity for the earlier generations to benefit from this as well. Using the tool of gamification as Hurka and Tasioulas (date) argue in “Games and the Good I will discuss the intrinsic value of game-playing as connected to a growth mindset to affect change within this discourse on historical knowledge and how school pupils can work with it. My departure point is process not product.

“Game-playing is the paradigm modern (Marx, Nietzsche) as against classical (Aristotle) value: since its goal is intrinsically trivial, its value is entirely one of process rather than product, journey rather than destination.” Hurka and Tasioulas (2006, p. 217)

Hurka and Tasioulas’s (2006) ideas on game-playing within an educational setting are important, because a lot of this work is based on looking at a growth mindset in these settings (Dweck,2006).

This document will be set up in four parts. I will start by introducing the content I worked with in my previous essay to give an understanding of the research done before about the Dutch Historical Curriculum and the need to make it a more inclusive experience. To make this into a gamified experience I had to look at the growth mindset (Dweck, 2006) where Dweck discusses the difference between a Growth and Fixed mindset and the need to implement this in educational settings. The second part will focus on four concepts in psychology that allow me to reflect on why my parents reacted negatively or not according to the script I had in mind when I introduced my essay to them. The third and final part of this thesis will focus on the game element of my practice project where I look at the Ludic Century (Zimmerman, 2014) and Critical play (Flanagan, 2009). In doing this I will see if I can use Dweck’s growth mindset in ludo didactics. For the logic in Dweck’s work (2016) has many similarities with the concepts of Zimmerman’s (2014) and Flanagan’s (2009) work. They all discuss; keeping the mind open to opportunities, rewarding process over rewarding a moment, and many more. Zimmerman and Flanagan speculate heavily about the future. In Zimmerman’s manifesto about the ludic century, he argues the coming century to be the century where we implement games and game-play even more in our daily life and most of us even become game-designers. Zimmerman (2014) states games are a way to create an attitude of a designer as thinking like a designer is essential to get a growth mindset. Creative thinking is something that opens the mind to embracing challenges, not to back down from changes, and think about things in new ways. Therefore in order to give the next generation a more inclusive frame of reference, I hope combining a revised Dutch history canon with a game element will create a growth mindset towards the historical curriculum. This way we can start to create an archive of inclusive history stories that can function as the premise on which the new revised history canon can be built upon.Part 1: How Education is used to Institute Indoctrination

To start the setting of the content of my previous essay I want to give 1 example of withheld Dutch history. Knowing this is a part of 1 of many examples of essential Dutch history that is absent from history books still today.

In the years 1926/1927 nationalist and communist groups formed in Java and West-Sumatra against the Dutch colonists. While being wildly outnumbered in a ratio of around 60 million to 200.000 the Dutch realized they were in trouble.2 They panicked so much that they arrested over 13.000 people. Four of them even got a death sentence and were hanged.3 Around 4.500 people got a jail sentence of a couple of months and were released after. For the rest of the people it was unsure what their involvement was exactly so the Dutch colonists decided to put these people in a very distant and isolated camp in what was Dutch New Guinea. What was important to the Dutch is that the camp would look very ordinary. Like another “normal” Indonesian village. This is what became Camp Boven-Digoel. This camp was something that in other terms would have been called a concentration camp. Back then (from a colonialist perspective) the only thing that was purposely promoted about the people that lived there - the Papoea - was that they were a savage species of people. They were only known for some stories by colonists that told they were famous for being dangerous headhunters. Purposely withholding information about the Papoean people. This act of reducing the Papoean people to one thing is something Agamben (1995) would define as “bare life” or “life which has been reduced to biology whilst the person’s political existence has been withdrawn by those who have the power to define who is included and who is excluded as worthy, sovereign human beings”.4 For this reason the prisoners of camp Boven-Digoel would think twice before trying to escape through the woods. The trip to the camp was a long journey, because of the bad connections they took even longer to get from Jakarta to Boven-Digoel than to get from Jakarta to the Netherlands. In an act of true desperation the prisoners that were on the ships sometimes tried to jump off them and drown themselves.5 In books written about camp Boven-Digoel like Louis Johan Alexander’s “Boven-Digoel” or I.F.M. Salim’s “Vijftien Jaar Boven-Digoel” you can find graphic details of what was going on in this concentration camp that the Dutch called a prison camp. For example Salim (date) writes about how from time to time a crocodile would come to a shore and grab one of the prisoners to disappear in the water again. Their bodies were never found. As most of the prisoners were wrongfully accused the camp is referred to in many books as a concentration camp. This is similar to the German camps in Amersfoort or Vught during the second world war.6

Analyzing why stories like these are not part of the Dutch canon starts with the way the canon is set up. It all starts with the department of education, which is part of the government. This department determines the boundaries set for what children should learn in school. The first step is to ask a group of established historians to determine what the key periods and figures every Dutch person should know are. So the department of education has set up a commission led by Dutch, white, male, modern-history expert Piet de Rooy to determine what Dutch students should learn about the Dutch history. This commission last met to discuss the content of the history curriculum in 2001, 18 years ago. The 10 key periods in time according to Piet de Rooy and his team are: (1500-1600) ‘discoverers and reformers’, (1700-1800) ‘wigs and revolutions’ and (1800-1900) ‘civilians and steam-machines’. Piet de Rooy’s commission also determined that theory should be limited to European and western history. After this another commission led by one of the most famous Dutch, white, male historians in the Netherlands Frits van Oostrom, made more additions to the Dutch historical curriculum. Adding the 50 most important Dutch people/objects/happenings in Dutch history. In 2010 this canon was a mandatory part of knowledge every student had to have in order to pass their exams.7

After this process, the department of education selects 4 publishers to start the making and printing of the historical educational books. The publishers pick their own writers who write the texts for the books. Who will receive a couple of sentences per time frame they have to abide by. With these sentences of information they have to fill a book. The final step which is something that especially for me as a graphic designer is an odd step. The step of printing a physical book which not only makes information outdated because it cannot be updated but also because by the time it has been printed we can be 6 weeks further.

I think the following changes need to be made to the curriculum as it stands, to make sure that subjects such as The Dutch Drug Cartel9, the involvement of the Netherlands in the transport and trading of slaves and slavery9, Dutch concentration camps in the former Dutch Indies9 and other valuable and important , subjects that are currently not included will be a part of my revised curriculum. Using analog books as a vessel to distribute important information in a time where computer technology is at the root of human existence and information and technology is available at your finger tips is something that should be obsolete. In this Information revolution11 something as important as a publication on history should be changeable and evolving overtime instead of being a “screenshot” of a re-frame of a re-frame of a re-frame of a re-frame.

Questioning “common sense everyday knowledge” such as the Dutch history books that I learned from when I was young is for me an essential part of what Dutch culture should be about. We need to break the Dutch idea that we are and should be this mono-ethnic and mono-cultural country. Many of the people who live in the Netherlands do not identify with this representation of the Dutch culture12. I, a Dutch, white male do not feel represented or identified by this portrayal of Dutch culture. So what I would like to propose is in order for the Dutch historical curriculum to represent diverse inhabitants it should show history in an inclusive way where we look at the “Dutch history book” as a more fluid publication that changes digitally and is not set in the frame of the analog book. So that the Dutch historical curriculum will serve as a vessel for cultural inclusiveness and future Afghan friends are not being bullied for not “being Dutch”.

Part 2: Growth and Fixed Mindsets (Dweck, 2006)

I started this study by reading various scholars on the subject of mental rigidity. “Reading intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s skills” (Simon Calmar Andersen & Helena Skyt Nielsen, May 18 2016). An experiment, where children who are fixed are being taught to read in a growth mindset way, praising the children's effort rather than the performance. This resulted in supporting the notion that a reading intervention with a growth mindset has a large potential for supplementing school’s effort to get children to read well and express themselves better in writing. “Navigating the Future: Social Identity, Coping, and Life Tasks” (Geraldine Downey, Jacquelynne S. Eccles and Celina M. Chatman, January 12, 2006), A book written collaboratively by various psychologists on social identity who state that identity is not something fixed but rather something fluid. They explore multiple situations where identity is being tested and when and where negative stereotyping comes in play. The authors argue that these experiences? can be mitigated by challenging these students educationally, expressing optimism in their abilities, and emphasizing that intelligence is not fixed, but can be developed.

Both works referenced above refer to Carol Dweck as their main source supporting their arguments. However there is also criticism of Dweck’s work due to lack of replicability. Many scholars such as psychology professor Timothy Bates have tried to replicate Dweck’s thesis without success due to the fragility of her experiment and the fact that it has to happen under strictly controlled conditions. In spite of the criticisms that have been made about her work, I am not interested in mimicking the circumstances of her experiment, but my interest lies in the implications of the logic of Dweck’s work (2006). Her work explores two mindsets: the Growth mindset and the Fixed mindset. These mindsets reflect how humans structure the self and guide their behaviour.

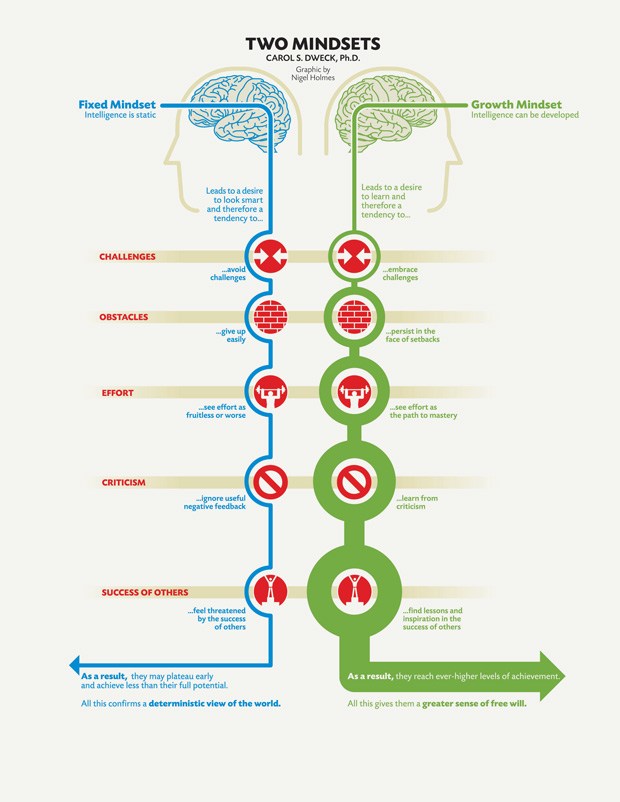

Fig. 1

If we look at figure 1 we see a schematic on the two mindsets discussed by Dweck. The two mindsets were tested on Dweck’s students via a variety of challenges, obstacles, effort, criticism and the success of others. It became clear that through her research Dweck could recognize these traits and how she incorporated them into the mindset traits shown in figure 1. As Dweck studied her students she could see that the ones with a more fixed mindset have a desire to look smart and therefore would more likely avoid challenges, give up easily, see effort as fruitless or worse, ignore useful feedback and would feel threatened by the success of others. As a result, they may plateau early and achieve less than their full potential (Dweck, 2016). This - the fixed mindset - it is often called or Dweck calls this a deterministic view of the world. This, Dweck argues, is different from students who have a growth mindset who have a desire to learn and therefore a tendency to embrace challenge, persist in the face of setbacks, see effort as a path to mastery, learn from criticism and find lessons and inspiration in the success of others. As a result they reach ever-higher levels of achievement (Dweck, 2016).

As modern societal values such as intelligence, personality and character are something that are culturally desirable it is normal for a human to have this fixed mindset. This is because societal standards are built to promote people who are intelligent, have personality and character. However, as Dweck writes.

“There’s another mindset in which these traits are not simply a hand you’re dealt and have to live with, always trying to convince yourself and others that you have a royal flush when you’re secretly worried it’s a pair of tens. In this mindset, the hand you’re dealt is just the starting point for development. This growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts.”(2016, p. 6/7)

This other mindset, the growth mindset is something that Dweck saw at a high school in Chicago. This high school actively tried to encourage the creation of growth mindsets. Instead of giving the students grades for individual courses the students had to pass a number of courses to graduate. However, when a student would “fail” a course they would get a bad grade but they would get the grade “not yet”. This is what Dweck refers to as “The Power of Yet”.

The power of yet helps students understand that they are on a learning curve instead of failing a student and making them think they are stuck in this moment of failure. This growth mindset Dweck could also see represented in some younger children that she gave the challenge of solving mathematical problems that were slightly too difficult for their educational level. Where some of them reclined in thinking they were never able to solve these equations. Some of the children said they loved a challenge and even posed they were hoping the questions would be informative. Making them understand that their abilities were something that could be improved.

To get a better understanding of the psychological aspects that induce and strengthen the fixed mindset I will, in chapter 2, explore the following work on: heuristics (Tversky, Kahneman, 1974), the Need For Cognitive Closure (NFCC) (Baban, 2014), and seizing and freezing (Kruglanski, Webster, Klein, 1993)

Part 3:

Herbert A. Simon, an American economist, political scientist and cognitive psychologist formulated the first concept similar to heuristics called “satisficing”. He first introduced this concept in his 1947 publication “Administrative Behaviour”. He uses the term satisficing to explain how human beings make decisions under circumstances in which the optimal solution cannot be easily determined. Tversky and Kahneman’s 1974 thesis “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” developed Simon's concept of satisficing and introduced the term “heuristics”. Tversky and Kahneman (1974) introduce three basic heuristic categories (i) representativeness, which is usually employed when people are asked to judge the probability that an object or event A belongs to class or process B; (ii) availability of instances or scenarios, which is often employed when people are asked to assess the frequency of a class or the plausibility of a particular development; and (iii) adjustment from an anchor, which is usually employed in numerical prediction when a relevant value is available.

Going back to the situation that prompted this research, my parents' negative reaction to the sense of urgency expressed in my minor project, one could say that the second heuristic, the availability heuristic, is a plausible frame for their response. It is possible that my parents did not understand or realize what the urgency of making the Dutch historical curriculum more inclusive was based on, due to the information available to them at a specific time. They had not received the correct information or not the full extent of the information so they had trouble understanding that the current history curriculum is not inclusive. Hereas heuristics are more specific categories on human decision making, need for closure by Kruglanski and Webster, is a concept based on understanding knowledge-construction processes in humans. As Kruglanski and Webster discuss in their 1996 thesis “Motivated Closing of the Mind: “Seizing” and “Freezing”, the need for closure is a trigger of the mind that is based on heuristics that make the mind search for this closure.

“The need for cognitive closure refers to individuals' desire for a firm answer to a question and an aversion toward ambiguity. As used here, the term need is meant to denote a motivated tendency or proclivity rather than a tissue deficit (for a similar usage, see Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). We assume that the need for cognitive closure is akin to a person's goal (Pervin, 1989). As such, it may prompt activities aimed at the attainment of closure, bias the individual's choices and preferences toward closure-bound pursuits, and induce negative affect when closure is threatened or undermined and positive affect when it is facilitated or attained.” (Kruglanski, Webster, 1996, p 264)

Looking at these concepts on growth and fixed mindsets, cognitive closure and heuristics that discuss the psychological aspects of decision making of the mind one has to look at contexts? where these decision making moments are being contested. Game-playing and gamification are ways to provoke and challenge new ways of evaluating normalized standards and ideas. Through looking at the work of Eric Zimmerman (2014) who characterizes the coming century as the “ludic century” or the century of games and states the importance of why this is a necessity and introducing Mary Flanagan’s work on “radical game design” I will continue to examine the value of game playing in group 7 and 8. Here the students have just finished the given history canon and will be using my project as an addition to this canon. This in order to unveil perspectives on history that are currently absent and create a database of perspectives that can be a base for the future.

Part 4:

Ludic Century and Game-Playing

To show the importance of game-playing I want to refer to Eric Zimmerman’s Ludic Century Manifesto, first published in Steffen P. Walz and Sebastian Deterding’s 2013 “The Gameful World: Approaches, issues and applications”. Zimmerman refers to the upcoming century as the Ludic Century due to the influence of games and game-playing in life. He states that games have been around for centuries, one could even say they are ancient. Games come in many shapes and sizes and are a characteristic feature of human societies. Games may perhaps be the first interactive system the human kind invented. Due to the rise of technology and the century of information. We live in a world of systems. There are many complex systems of information at play nowadays. These systems influence the way we communicate, research, learn, socialize, find partners be they romantic or sexual, conduct our finances and communicate with governments. If one would look at this, one could state that for such a society controlled by systems, games would make a perfect fit. The attitude we need to inhabit in this world of systems has to be an active one. Which I also see as the attitude of a designer. Offering us a way to engage with the world around us. Games are a literacy, literacy is about creating and understanding meaning, which allows people to write (create) and read (understand). Game literacy can address the issue of the Dutch history curriculum being one of indoctrination. Gaming is a mentality and playfulness is an attitude. One that I will include in my practical project by thinking of researching in a playful way. Making research and history lessons into something gamified. Social issues such as the institutional racism that is still in every layer of our society refusing some human beings the most basic human rights. These are just two examples of the problems the world has these days. This is something that requires a type of thinking that gaming literacy can provide. It can provide this complex systemic society with a playful, innovative, transdisciplinary way of thinking where the systems can be analyzed, redesigned and transformed into something better. In the context of the Dutch canon this could be something that does not show one perspective as it does now. This could be the addition of a story of multiple perspectives that create inclusiveness.

In the ludic century, Zimmerman argues everyone is going to be a game designer as game design provides a logic of systems, social psychology, and culture hacking. Thinking of new ways to modify it and keep evolving. The many facets games offer are what will make the next century the Ludic Century, Zimmerman argues. He concludes that games are something beautiful and as such they do not necessarily need to be justified and be much more important. Like many other forms of cultural expression, game-play is also important because it is beautiful.

“Appreciating the aesthetics of games — how dynamic interactive systems create beauty and meaning — is one of the delightful and daunting challenges we face in this dawning Ludic Century.”(2014, p. 22)

Flanagan’s (2009) work is different from Zimmerman’s in that she focuses on the value of game-play. Where Zimmerman’s work focuses on the importance of gaming in today’s and tomorrow’s society at an abstract level. Flanagan however, focuses on how to create valuable moments in designing games and is a useful addition to the development of my thinking on how to implement changes within an educational setting. Flanagan’s (2013) work on Critical Play in the context of radical game design is important for many reasons that I will discuss in the next section.

Mary Flanagan: artist, author, educator, designer and pioneer in the field of game research and critical play. Flanagan’s work on critical play in the context of radical game play is based on her PhD dissertation and describes how artist and activists have used games to facilitate social critique. Most games are used as a vehicle for distraction, enjoyment, relaxation and imagination. Flanagan wants to use this vehicle that most people love and are interested in and show how it has been used for creative expression, conceptual thinking and can serve social change. Flanagan (2009) examines games that challenge the norms of gaming and thus the norms of a society. In the book “Radical Game Design”, she provides a critical play method based on the needs of game design and the importance of iteration. Flanagan states that iterative design in the context of game design is essential in creating valuable game-play and was based on ideas from artists’ games over the last century. The steps for this iterative design are as follows.

“I. Set a design goal (also known as a mission statement). The designer sets the goals necessary for the project. Ii. Develop the minimum rules necessary for the goal. The game designers rough out a framework for play, including the types of tokens, characters, props, and so on. Iii. Develop a playable prototype. The game idea is mocked up. This is most efficiently done on paper or by acting it out during the early stages of design. Iv. Play test. Various players try the game and evaluate it, finding dead ends and boring sections, and exploring the types of difficulty associated with the various tasks. V. Revise. Revising or elaborating on the goal, the players offer feedback, and the designers revamp the game system to improve it. Vi. Repeat. The preceding steps in the process are repeated to make sure the game is engrossing and playable before it “ships” or is posted to a website.”(Flanagan, 2013, p. 289-299)

This way of circular design that keeps on improving and changing the game is essential to creating meaning in a game for it uses the “not yet” method by Dweck. By making use of this iterative design method you not only make the players, but also the designers conscious of the fact that something set in time and a result measured from one moment is not beneficial to growth. Using this iterative design method in the practical part of the game I have developed will make sure that the game will continue to evolve and grow over time and not be a product of a moment. So as not to reproduce the weaknesses of the current Dutch historical curriculum - where the history that is taught has not changed in over 30 years.

Reflexive Summary

In the beginning of this thesis I asked the question. Why did my parents not fully understand the urgency of having a more inclusive Dutch historical curriculum? Why did they respond to my earlier essay the way they did? I had written about the faultiness of the Dutch historical canon. Which is faulty in the way it tells a particular story from a largely white western colonist view of the Dutch history. Leaving out many stories and perspectives. In writing about that subject, an understanding of the urgency rose up within me - this had to change. When talking about this with my parents they did not share this same feeling of urgency. Looking to understand why they did not share this feeling the research split in several directions. Starting my research I looked at cognitieve research on growth and fixed mindsets (Dweck, 2016). Followed by heuristics (Tversky, Kahneman, 1974), the Need For Cognitive Closure (NFCC) (Baban, 2014), and seizing and freezing (Kruglanski, Webster, Klein, 1993). With a final consideration of games and game-play I examined work on the Ludic century (Zimmerman, 2014) and radical game design (Flanagan, 2009). All these works including the research I have done in my previous essay on “The Dutch Historical Curriculum: How education is used to institute indoctrination enabled me to see that there is a connectivity throughout these theories that support and build upon Dweck’s ideas of a growth mindset and how the power of yet can help students in educational settings can work and make decisions in a more meaningful way with an eye to the future.

Going back to my original question I now understand that the Dutch historical curriculum is enabling fixed mindsets on the topic of Dutch history. By using information that has been set in time for many years, information that is not open to change or open to additional information. Where the Dutch history is still privileging a white western mono-cultural perspective stuck in time - there is a need for change. Realizing this I have contacted the Black Archives an Amsterdam based initiative who have drawn attention to the need for new history canon in Dutch schools. Their proposal is a valuable addition to my thinking on this issue, particularly regarding the content I as designer can work with. This need to create a more inclusive Dutch canon on history is one that I want to embed in my practice project. Due to the research on game-play and games I can say that creating meaningful interaction between parties is easily accomplished. Which is the reason the project will have a game element. The root of the problem I am working on is the Dutch educational system and how the history canon is set up and I want to tackle the issues at the epicenter. Implementing the theory of Dweck and her growth mindset into the mechanics of the game, so that the children who just received the first part of information on the Dutch history in class, will reveal the rest of the history that is absent in Dutch historical schoolbooks. In this I follow Dweck: always leaving room for growth.

Conclusion as ongoing collaboration

As I discuss in my 2019 essay “How education is used to institute indoctrination”. The Dutch history book is outdated in an age that is often referred to as the “Information Age” (J.D. Bernal, 1939). In order to give the teaching of Dutch history more context and make it more inclusive I decided to look at the articles/archive of The Correspondent in collaboration with the Black Archives. The latter have published multiple articles on “de verzwegen geschiedenis van Nederland” or the withheld history of the Netherlands. In a collaboration project with the Black Archives, we have decided to work on a game that teaches the audience to create a growth mindset when it comes to learning history. This in learning connectivity through time is essential in order to understand what is going on in the world right now. What, led to what. As a base for this I will be using the new Dutch history canon proposed by the Black Archives “10 times more history”. This proposal is a canon that cancels the mono-cultural white western one that is at place at the moment and replaces this with a more culturally diverse version. One with more than the white Dutch perspective. In doing this and knowing that even this information is not all of the information, one must keep the game open to change. Open to even more perspectives so that the Dutch Historical curriculum can become something that teaches all of the inhabitants of the Netherlands the history of all of the inhabitants of the Netherlands.

“...the Netherlands looks at its postcolonial citizens: “still not taken seriously, not their past of slavery, nor their present presence in this country” (De Swaan 2013, 6).” (Wekker, 2016, 14)

Bibliography

http://www.theblackarchives.nl/meergeschiedenis.html

In a 2014 TED Talk, Dweck talks about the power of Yet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_X0mgOOSpLU&t=337s Kuyper, D. (2020, May 5). The Dutch Historical Curriculum. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://beyond-social.org/wiki/index.php/The_Dutch_Historical_Curriculum

Li, Y., & Bates, T. C. (2019). You can’t change your basic ability, but you work at things, and that’s how we get hard things done: Testing the role of growth mindset in response to setbacks, educational attainment, and cognitive ability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(9), 1640–1655. doi: 10.1037/xge0000669

Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: the new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

Walz, S. P., Walz, S. P., & Deterding, S. (2014). The gameful world: approaches, issues, applications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Flanagan, M. (2013). Critical play: radical game design. Cambridge MA: Mit Press.

Wekker, G. (2016). White innocence: paradoxes of colonialism and race. Durham: Duke University Press.

Salim, I.F.M. Vijftien Jaar Boven-Digoel: Concentratiekamp in Nieuw-Guinea: Bakermat Van De Indonesische Onafhankelijkheid. Smit Van 1876, 1980.

Buxant, Coralie, and Vassilis Saroglou. “Feeling Good, but Lacking Autonomy: Closed-Mindedness on Social and Moral Issues in New Religious Movements.” Journal of Religion and Health, vol. 47, no. 1, Oct. 2007, pp. 17–31., doi:10.1007/s10943-007-9142-1.

Thórisdóttir, Hulda, and John T. Jost. “Motivated Closed-Mindedness Mediates the Effect of Threat on Political Conservatism.” Political Psychology, vol. 32, no. 5, 2011, pp. 785–811., doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00840.x.

Oller, D. K., et al. “Functional Flexibility of Infant Vocalization and the Emergence of Language.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 16, Feb. 2013, pp. 6318–6323., doi:10.1073/pnas.1300337110.

Hurka, Thomas. “Games and The Good.” Drawing Morals, Nov. 2011, pp. 185–198., doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199743094.003.0011.

Mcnemar, Olga W. “An Attempt to Differentiate between Individuals with High and Low Reasoning Ability.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 68, no. 1, 1955, p. 20., doi:10.2307/1418387.

Roets, Arne, and Alain Van Hiel. “Need for Closure Relations with Authoritarianism, Conservative Beliefs and Racism: The Impact of Urgency and Permanence Tendencies.” Psychologica Belgica, vol. 46, no. 3, Jan. 2006, p. 235., doi:10.5334/pb-46-3-235.

Lalwani, A. K. (2009). The Distinct Influence of Cognitive Busyness and Need for Closure on Cultural Differences in Socially Desirable Responding. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(2), 305–316. doi: 10.1086/597214

Heimbuch, S., & Bodemer, D. (2019). Effects of the Need for Cognitive Closure and guidance on contribution quality in wiki-based learning. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/8c45p

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing.”. Psychological Review, 103(2), 263–283. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.2.263Robbins, B. (2011). Microscope: a fractal role-playing game of epic histories. U.S.: Lame Mage Publications.

Links

CONTRIBUTE

Feel free to contribute to Beyond Social.